Episode 087: Disorganized Attachment: Fear without Solution

By listening to this episode, you can earn 1 Psychiatry CME Credits.

Other Places to listen: iTunes, Spotify

Article Authors: Annabel Kuhn, BA, David Puder, MD

There are no conflicts of interest for this episode.

Why Is Disorganized Attachment Important To Learn About?

Infant disorganized attachment is associated with dissociative symptoms in adolescence and adulthood.

“The only clear connections between infant attachment and adult psychopathology are between disorganized attachment and dissociative symptoms in adolescence and early adulthood (Dozier et al. 2008a). (Shemmings & Shemmings 2011, p.62)

15% of infants in middle-class, and 34% in low income samples have disorganized attachment (van IJzendoorn et al. 1999)

When people dissociate, it means they feel disconnected from their body. They feel fear and dread, sometimes feeling completely frozen. Some patients who have a history of trauma will appear to have panic attacks, but the symptoms have a more dissociative nature rather than just pure panic. Because of less awareness around dissociation, it’s possible for patients to describe a more dissociative experience even if they first label it as panic.

What Is Disorganized Attachment?

Disorganized attachment is a category assigned to children who exhibit specific behaviors during the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP). The Strange Situation Procedure is a standardized procedure created by Mary Ainsworth to observe attachment patterns of infants with their caregivers. It can be performed with children between the ages 9 and 18 months. The strange situation procedure involves a caregiver leaving an infant in a new environment with interesting toys. The caregiver leaves the room twice; the first time the infant is left with a stranger, and the second, the infant is left alone. Attachment patterns are characterized by the infant’s interaction with his or her carer upon the carer’s return to the room.

OTHER ATTACHMENT RESPONSES TO THE SSP

In a secure attachment reaction, the infant would approach the caregiver when they reentered the room. The infant might cry for about 30 seconds and then stop once they were consoled by the caregiver. Then the infant would immediately exhibit feelings of joy and return to playing within 1-2 minutes

In the avoidant pattern, an infant shows a delayed inclination to approach their caregiver, “regulating themselves through a focus on toys” (Duschinsky & Solomon, 2017) The child’s most adaptive behavior is to observe their mother while regulating with their toys

In the ambivalent/resistant pattern, an infant displays anger/passive helpless distress to maintain the attention of their caregiver

DISORGANIZED ATTACHMENT RESPONSE

In a disorganized attachment style, the child’s response can be best thought of as “fear without solution,” in that the child is afraid of external situations, but is unable to find comfort from a caregiver. An infant with disorganized attachment for example may initially go towards the carer, and then shy away. The child lacks an organized strategy to deal with the stress of separation.

“‘Disorganized attachment’ is a precise term that must involve a situation which mildly activates the child’s attachment system and in which a carer is ‘introduced’, either physically as in the SSP (strange situation procedure), or by asking the child to think about that carer” (Shemmings & Shemmings 2011 pg 39).

Other examples of disorganized attachment behaviors as noted in Cassidy & Shaver 2016 are:

Displaying contradictory behavior

Very strong attachment behaviors followed by avoidance, freezing or dazed behavior

Avoidance behaviors and concurrent contact behaviors (seeking, distress, anger)

Unusual movements and stereotypies

Extensive expressions of distress accompanied by movement away from, rather than towards the mother

Stumbling, but only when the parent is present

Freezing or stilling and slowed “underwater movements” or expressions

Trance-like expressions

Display of apprehension of the caregiver

Hunched shoulders or fearful facial expressions

Overt signs of disorientation or disorganization

Disoriented wanderings, confused/dazed expressions

Multiple rapid changes in affect

These behaviors are also consistent with adult dissociative disorder. Some patients in our intensive outpatient program will have psychogenic seizures that can last between 30 minutes to 2 hours as opposed to normal seizures, which last about 2 minutes. An episode which lasts for 2 hours per day is probably more of a psychogenic seizure, also called a dissociative seizure. I discussed dissociation prior in my episode on the polyvagal theory, in which I discussed how the dorsal vagal system is active and a person is stuck in shut down.

What Does Disorganized Attachment Look Like Throughout Childhood and Adolescence?

DISORGANIZED ATTACHMENT IN A 4 MONTH OLD

A 2010 study explored attachment patterns for 84 caregiver-child dyads. When the child was 4 months of age, face-to-face interactions within the dyads were videotaped and coded for attention, emotion (facial and vocal affect), orientation, and touch.

It’s important to recognize that the interaction is always a dyad or a back and forth between the mother and the infant. In secure attachment for a 4 month old child, if the infant smiles, is distressed, or wants space, the mother will react positively with a smile, concern, and give the child space. There is a constant interaction and response between the infant and the mother.

In contrast, the future disorganized child may look angry, look away, want space, or express happiness while the mother’s reaction is typically demonstrating surprise, looming in, or expressing anger. Ultimately, there is a mismatch occurring between the infant and the mother.

When children who displayed disorganized attachment at 4 months old were re-surveyed at 12 months of age, the dyads were put through the strange situation procedure. What they found was that communication/microexpressions at 4 months was able to predict attachment patterns at 12 months (Beebe 2010).

Figure 6. Illustrations of disorganized attachment.

“Note: Although the mother and infant are shown as if side by side, they are filmed facing each other. Frames (1) and (2) comprise a sequence, 3s apart (24, 27). Frames (3) and (4) are taken from separate sections of the interaction. Frames (6–8) comprise a 4s sequence (59, 01, 02) illustrating high mother face self-contingency, ‘‘stabilized face.’’ Frames (9–10) comprise a 2s maternal loom sequence (18, 19). Frames (11–14) illustrate a second maternal loom sequence across 3s (50, 51, 51, 52),” (Beebe 2010).

For infants coded as “disorganized” at 12 months, their interactions with their mothers at age 4 months were characterized by:

Less frequent affectionate touch between mother and child, (sometimes the infant was never touched)

Infant touched himself or herself less frequently

Infant was more distressed (as measured by facial expression/voice)

Infant more angry, protesting, crying

Discrepant, contradictory, conflicted affects (between positive and negative in less then one second).

Example: smile and whimper in less then one second

Mother looked away for longer periods and unpredictably or loomed in more

Mother did not follow the infants emotions

Mother positive (smiles or suprise) when infant was distressed

Less likely to be positive when infant positive

Mother demonstrated still face; overly facially stable

Mother displayed spatial intrusion (“loom” and “chase and dodge”)

These studies emphasize the importance of the first months in a child’s life. New parents will sometimes have a hard time understanding the importance of connection with their newborn, but when they see this study it gives them an idea of how crucial early interaction is. There are plenty of reasons why people are severely disconnected, which ends up disrupting the dyad.

(Beatrice Beebe is a great researcher of early development, including affective mirroring and the power of the diad in psychotherapy. Here is one book I recommend)

DISORGANIZED ATTACHMENT DURING MIDDLE CHILDHOOD

Children who were characterized as having disorganized attachment patterns during infancy have been described as exhibiting controlling behavior toward parental figures and caregivers during childhood.

Behavior by age 8 largely depends on family dynamics. A child categorized as having disorganized attachment at 12 months were more likely to exhibit punitive and disorganized behavior at age 8, but only within families with clinical risk factors.” (Bureau et al., 2009). (This study considered families to have “clinical risk factors” if they had been “referred for clinical home visiting [...] because of concerns about the quality of parent-infant relationship”.)

A 2012 study determined that callous-unemotional traits between ages 3-8 years old were significantly associated with disorganized attachment (Pasalich 2012).

According to this study, children with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits appear to be disconnected from the emotions of others, pay less attention to others emotions and are less responsive to other’s emotions and lack empathy.

The study consisted of 55 boys ages 3-9 years (M=6.31 SD=1.80) who were referred for conduct problems.

The overall model was significant: F(3,51) = 6.18, p < .01; and accounted for 22% of variance in disorganisation.

High levels of callous-unemotional traits were:

associated with disorganized style attachment (accounting for between 26% and 36% of variance.)

x2(3) = 16.70, p < .01

“As hypothesised, children with higher levels of callous-unemotional traits were more likely rated as disorganised in their attachment representations” (Pasalich 2012).

DISORGANIZED ATTACHMENT DURING ADOLESCENCE

Studies have repeatedly demonstrated the connection between dissociative disorders and disorganized attachment (see Carlson 1998; Liotti 2004; Sroufe et al 2005). Dissociation symptoms extend beyond adolescence and into adulthood, as we will discuss in a later section.

Dissociation, (as the name suggests) is characterized by a dissociation of consciousness. Minor dissociative states are commonplace, for example, becoming so absorbed in listening to The Psychiatry and Psychotherapy Podcast on your drive that you are unaware of the passing landscape. Dissociative disorders, in contrast, involve dissociation of one’s identity, memory, and consciousness (Cassidy & Shaver 2016).

It’s normal to experience this to some degree. Sometimes we may enter a room and completely forget what we needed, but imagine ending up somewhere without any recollection of the previous two hours that got you to your destination. Another example of dissociation is intense depersonalization where a person freezes and feels completely separate from their body.

Ogawa & colleagues describe dissociation beautifully: “How often have you found yourself in some location but do not remember how you got there? Many people would say that they have experienced this situation, but infrequently. Imagine, however, if that happened to you quite often. That is the paradox of psycho-pathological dissociation: many of the symptoms are common behaviors or experiences that are taken to extremes, which is why the developmental psychopathology perspective is pertinent to a discussion of dissociation,” (Ogawa 1997).

Conceivably, children who exhibit disorganized attachment in the Strange Situation, do so because their parent figure is unable to provide comfort/reassurance, because the parent may frequently display frightened/frightening behavior at home as a result of unresolved trauma. Disorganized children may dissociate because they have no opportunity to be consoled in the face of stressful situations. For these children, the person who is supposed to be comforting them is actually scary and frightening to them.

According to Carlson 1998, infant disorganization was associated with higher rates of dissociative behavior in both elementary and high school, as perceived by teachers (using the Teacher Report form of the Child Behavior Checklist).

Also, participants who displayed disorganized attachment in infancy self-reported more dissociative experiences on the Dissociative Experience Scale (DES) at Age 19 (Carlson 1998).

The Dissociative Experience Scale is a questionnaire that screens for dissociative symptoms.

“The higher the DES score, the more likely it is that a person has a dissociative disorder. [...] A score of more than 45 suggests a high likelihood of a dissociative disorder alongside a reduced likelihood of a ‘false positive’” (Dissociative Experience Scale)

If one has a high DES score, a more time consuming Structured Clinical Interview (SCID-D) can be used for diagnostic purposes.

There are 28 questions, and the patient response involves selecting a percentage that corresponds to how much he or she can relate to a given situation described in the question.

For example, question 25 reads “Some people find evidence that they have done things that they do not remember doing. Select a number to show what percentage of the time this happens to you.” (Dissociative Experience Scale)

Below are the results from (Carlson 1998):

In regression analyses, attachment disorganization ratings and elementary school behavior problem scores contributed significantly to the prediction of dissociation in adolescence. The combined set of variables produced a multiple correlation of .42, accounting for 17% of the overall variance

As clinicians, this helps us understand that dissociative patients need attunement, empathy, and connection. For instance, in order to help people attune to their real self (not just their mental illness as a label), we avoid giving energy to the illness narrative which may have been used for connection in the past. We want to give energy to the narratives that we see are real and healthy.

Plenty of people in our society, particularly women, learn early on that it is better not to demonstrate anger. You may have a patient who is always polite, but flashes microexpressions of anger while they speak. This could show that they have dissociated from their anger. Anger, however, isn’t always a negative emotion. Anger produces boundaries and gives us courage to have a voice. But, when children are not mirrored they don’t know what they feel, leading them to dissociate from emotions in their adulthood.

Many studies agree that dissociation is a major consequence of disorganized attachment. In fact, a 2008 study reports, “The only clear connections between infant attachment and adult psychopathology are between disorganized attachment and dissociative symptoms in adolescence and early adulthood.” (Dozier et al. 2008a).

Disorganized Attachment In Adulthood

The SSP (Strange Situation Procedure) classifies attachment patterns in infancy, while the AAI is used for attachment classification in adults. If an infant is classified as disorganized in the SSP, what is his or her classification on the AAI later in life?

One meta-analysis that assessed continuity from infant disorganization to AAI in adolescence or adulthood, found that disorganized infants were more likely to be classified as insecure or unresolved on the AAI at age 19. (van IJzendoorn, 1995). Unresolved/disorganized status on the AAI is now considered to be a direct equivalent of disorganized attachment patterns during the strange situation procedure.

What classifies someone as “Unresolved/Disorganized”?

This person displays “lapses in the monitoring of reasoning or discourse when discussing experiences of loss and abuse. These lapses include highly implausible statements regarding the causes and consequences of traumatic attachment-related events, loss of memory for attachment-related traumas, and confusion and silence around discussion of trauma or loss,” (Levy 2006).

This is the “adult form” of disorganized attachment

This in contrast to “secure attachment” on the AAI:

What classifies someone on the AAI as a “Secure/Autonomous Individual”?

This person will present a well-organized, coherent description of early attachment relationships, and freely express emotions and discuss concrete examples when discussing both positive and negative early relationships. They view attachment based relationships as being very influential to their own personal development. (Levy 2006)

(Other patterns of adult attachment that will not be detailed here include: dismissing, and enmeshed/preoccupied.)

Possible Long-Term Consequences of Disorganized Attachment

“PERSONALITY DISTURBANCES”

John Bowlby, one of the original pioneers of attachment theory, believed that attachment difficulties early in life predisposes individuals for personality disturbances later in life (Bowlby 1977).

Disorganized behavior in infancy may shift to controlling behavior that can extend into adulthood (Jacobvitz & Hazen 1999). Individuals with disorganized attachment feel as though they are powerless, and as a result, often see their peers as a potential threat. Behavior with peers shifts between extreme social withdrawal and extreme aggressive behaviors. (Jacobvitz & Hazen 1999). Individuals with disorganized attachment behavior are perceived by peers as “weird” or “annoying,” and as a result are subject to peer isolation and social rejection (Jacobvitz & Hazen 1999).

Early research suggested potential personality problems may arise as a function of disorganized attachment.

DISSOCIATION

As discussed above in the section surrounding adolescence, dissociation is a major consequence of disorganized attachment during infancy. Dissociation may initially present in adolescence and continue to exist into adulthood.

Individuals who displayed disorganized attachment behavior in infancy displayed dissociative symptoms in adulthood (Carlson 1998). Other causes of dissociation include various types of abuse. People with severe abuse may have severe dissociative disorders (as high as 97% of them). (Putnam 1991). This article is specifically talking about multiple personality disorders (now in DSM-V called dissociative identity disorder). People with multiple personality disorders have a high level of dissociation and trauma. The more trauma a person experiences, the worse dissociation is going to be.

One study suggests that disorganized attachment behaviors in childhood are phenotypically similar to dissociative states in adulthood (Liotti 2004).

“For instance, in the middle of an approach behavior to the parent, they may suddenly become immobile, unresponsive to the parent’s call, with a blind look, and persist in this state for 30 [seconds] or more,”(Liotti 2004).

“Since disorganized attachment in children is strongly linked to unresolved AAI ratings in their parents, these observations hint at the possibility of an intergenerational transmission of dissociative mental states that is related to unresolved memories of past parental traumas,” (Liotti 2004).

INTERGENERATIONAL TRANSMISSION OF TRAUMA

There is an intergenerational transmission of trauma, which means that if the parent has an unresolved adult attachment interview, unresolved trauma, they are more likely to have children with disorganized attachment. If you have trauma in your background and hope to have kids in the future, the best gift you can give them now is to work through your own trauma in therapy. Patients who have worked through their trauma using psychotherapy report their experiences differently in the adult attachment interview.

There’s a Jewish saying: “The sins of the parent go on to the third and fourth generation,” which science tells us often rings true. For example, If you have a father who sexually abuses their child, that child (without help and therapy) will be more likely to have disorganized attachment style, which will affect their children. That’s three generations affected by trauma. Intergenerational trauma can be difficult to get out of.

BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER (BPD)

Dissociation can be a symptom of borderline personality disorder. Borderline Personality Disorder consists of prolonged episodes of dissociation that are hard to break out of. BPD responds well to treatment where there is prolonged deep connection between the patient and the medical professional such as: mentalization, transference focus therapy, or dialectical behavior therapy.

There are correlations with infant and childhood DA which may possibly reflect more of the externalizing form in which DA becomes transformed as children get older when they need to inject predictability into their experience of being parented.” (Shemmings & Shemmings 2011, p.64)

A 2009 longitudinal study (N =162) found that disorganized attachment in infancy predicted symptoms of borderline personality at age 28 years (Carlson 2009).

Z = 2.12, p < .05

However, a study that was published four years later suggests that disorganized attachment in infancy does not predict BPD symptoms later in life, but it is rather disorganized attachment in middle childhood that is predictive of BPD symptoms, (Lyons-Ruth 2013). This shows that disorganization in infancy can be reversed. The disorganized behavior in middle childhood is more predictive of BPD. If the problem is not resolved by middle childhood, it probably won’t be resolved in that family structure. In these circumstances, it is not helpful to penalize parents by taking the child away as you would in instances of abuse. Taking the child away could actually make the situation even worse for the child. Helping the parent connect with their child is far more beneficial.

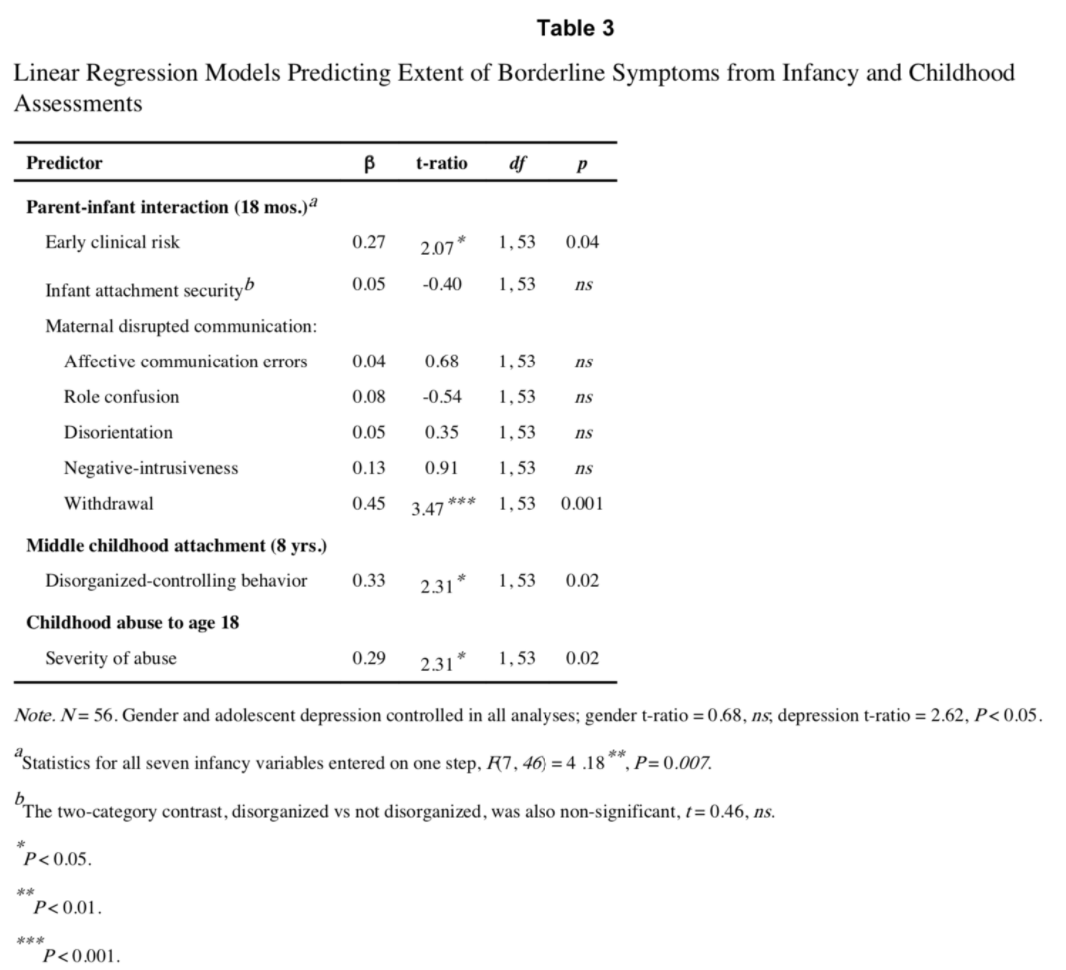

“Security of the infant’s attachment behavior was not a significant predictor of borderline symptoms (See Table 3 below) [...] Thus, the quality of maternal caregiving behavior in infancy, [...] provided stronger prediction of later borderline symptoms than assessment of infant behavior alone,” (Lyons-Ruth 2013).

“A linear regression model, controlling for gender and major depression, confirmed that disorganized-controlling behavior at age 8 was also a significant predictor to the extent of borderline symptoms at age 20 (see table 3 below). To illustrate this finding, we dichotomized the sample into those with and without borderline traits (2 or more symptoms). Among children who displayed combinations of disorganized and controlling behavior at age 8 (punitive, caregiving, disorganized), 43.5% displayed borderline traits in adolescence, compared to 15.3% of those elevated on only one scale, and none of those with low scores on all three scales. Thus, children with combinations of controlling and disorganized attachment behaviors at age 8 were more likely to display borderline symptoms in adolescence,” (Lyons-Ruth 2013).

Of note, because depression and BPD are so commonly seen together, controlling for depression might have overly controlled for BPD. The study did find severity of abuse was associated with BPD.

Controlling-punitive behavior:

Attempts to assert authority over parent using harsh commands or belittling comments

Controlling-caregiving behavior:

Directing the parent’s activities by guiding, encouraging, or structuring the parent

“Disorganized controlling child behavior at age 8 contributed independently to the prediction of borderline symptoms,” (Lyons-Ruth, 2013)

Disorganized-controlling behaviors in middle childhood attachment (8 years old) predicted BPD symptoms (Beta 0.33, p = 0.001)

Controlling-punitive/caregiving behavior incorporates role reversals between the parent and child. In controlling-punitive behavior the child is in control of the household. In the controlling-caregiving the child becomes the therapist, encourager, and creates structure for the dysfunctional parent. It is crucial for children to have boundaries and know the parent is in control or the dyad will be reversed to an unhealthy level.

Also, there are separate subtypes of disorganized attachment during infancy that are distinct in their ability to predict later suicidality and overall borderline symptoms.

The pseudo-secure subtype was a specific predictor of suicidality at age 20, (Wald = 4.82, P = 0.03), but not of overall borderline symptoms (t = 1.58, P= 0.12) (Lyons-Ruth 2013).

Suicidality can be a symptom of borderline personality disorder

The avoidant/ ambivalent subtype was not predictive of either borderline symptoms or suicidality (BPD symptoms t = -0.47, P=.64; Suicidality Wald = 1.77, P =0.18),” (Lyons-Ruth 2013).

(Table 3 from Lyons-Ruth 2013)

Sometimes people will have psychosomatic borderline personality disorder that will not show up in normal screenings. They use the medical system to get their psychological and attachment needs met. They may have controlling-punitive behavior by using their illness to maintain control rather than yelling.

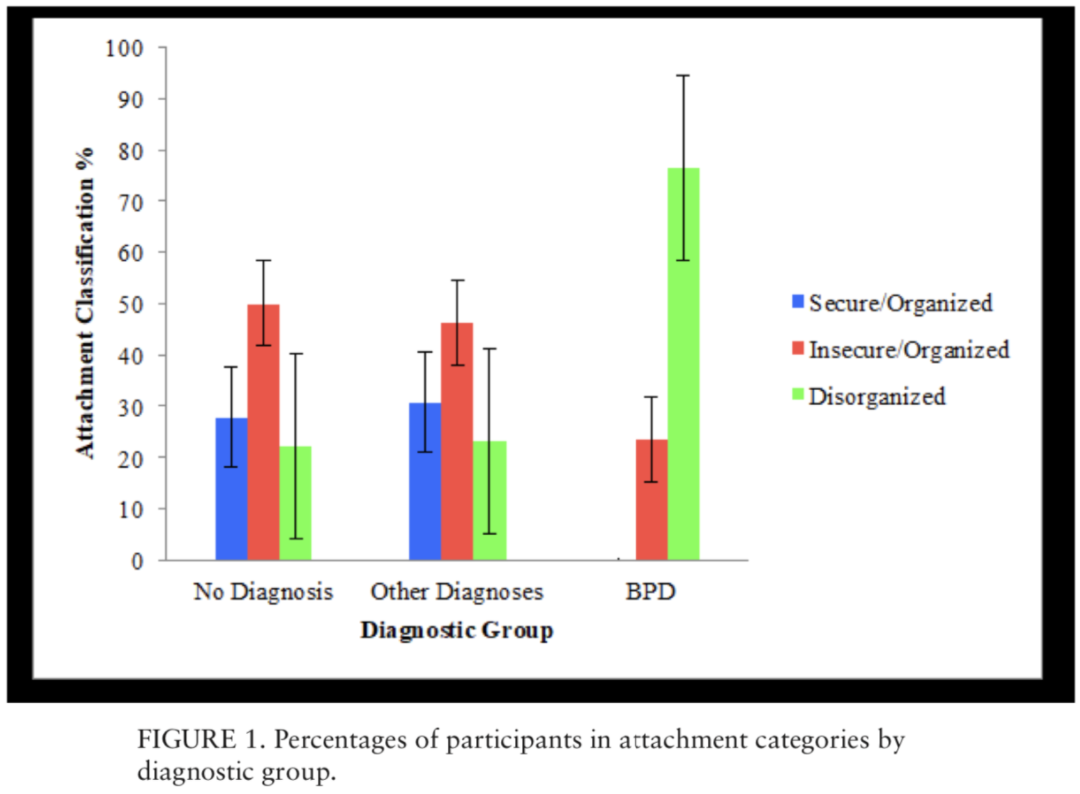

Furthermore, in agreement with the above data from Lyons-Ruth 2013, a more recent study reported disorganized behavior (after infancy) co-exiting with borderline features. Individuals with borderline personality disorder (n =17) had a greater likelihood of disorganized attachment behavior with their caregivers as compared to two control groups (control group 1= individuals with depressive, anxiety, or substance use diagnoses (n =13) , group 2=individuals with no diagnosis (n = 36), (Khoury 2019).

In this study, attachment security was measured using the Goal-Corrected Partnership in Adolescence Coding System (GPACS) which was developed in order to assess attachment patterns in adolescence.

Participants were between the ages 18 and 28 (M = 21.12, SD = 2.31).

“The odds ratio for disorganized attachment among BPD participants was almost 8 times that of participants without BPD,” (Khoury 2019).

BPD Group was significantly more likely to have less secure attachment than the “Other Diagnoses” Group

β = 2.26, SE = .72, Wald (df = 1) = 9.77, p < .01 (see figure 1 below)

BPD Group was also significantly more likely to have less secure attachment than the “No Diagnosis” group

β = 2.49, SE = .81, Wald (df = 1) = 9.47, p < .01 (see Figure 1 below).

Furthermore, there were no significant differences in attachment security between the “No Diagnosis” and “Other Diagnoses” groups

β = .19, SE = .63, Wald (df = 1) = .08, p = .77

All participants in this study were female given the high prevalence of BPD in females, so a limitation of this study is the inability to analyze gender differences.

While we know of many therapies that are beneficial for BPD (ie, DBT (Dialectical Behavior Therapy)), it may be beneficial for a disorganized patient to participate in disorganized attachment-specific interventions.

Dialectical Behavior Therapies are helpful for someone with BPD in part because the therapists have a counter transference process group to go over their own conflicts with handling the emotions that come up. Patients learn how to process their emotions so that it is not overwhelming. In Mentalization and Transference Focused Therapy, the focus is on the interpersonal—what is happening between them and their client.

In Summary

As mental health professionals, understanding disorganized attachment gives us appreciation and understanding for the necessity of empathy, attunement and deeply understanding the experience of another. Both their positive and negative emotions are important, and gathering the scope of their lives is crucial to building a good relationship with them.

In my episodes on microexpressions, I talk about the importance of recognizing small moments of emotion that will allow you to better attune to other people’s experience.

Episode 017: Microexpressions in Psychotherapy Part 3

Episode 016: Microexpressions: Fear, Surprise, Disgust, Empathy, and Creating Connection Part 2

Episode 015: Microexpressions to Make Microconnections Part 1

In my episodes on therapeutic alliance, I discuss the importance of empathy and being present to journey with the patient and creating a partnership and understanding of the patient’s subjective reality.

Episode 028: Therapeutic Alliance Part 1

Episode 032: Therapeutic Alliance Part 2: Meaning and Viktor Frankl’s Logotherapy

Episode 036: Therapeutic Alliance Part 3: How Empathy Works and How to Improve It

Episode 041: Therapeutic Alliance Part 4: What is Transference and Countertransference?

Episode 062: Therapeutic Alliance Part 5: Emotion

Episode 069: Therapeutic Alliance Part 6: Attachment Types and Application

Episode 070: Connecting with the Psychotic Patient, Therapeutic Alliance Part 7

I hope this episode provides the depth to understand the early empathy required to give someone a secure attachment. If the patient did not have that, we can help them be able to find ways to have healthy relationships through a healthy therapeutic alliance.