Episode 086: Free Will in Psychiatry & Psychotherapy Part 3

By listening to this episode, you can earn 1.5 Psychiatry CME Credits.

Other Places to listen: iTunes, Spotify

Article Authors: Matthew Hagele, MA, David Puder, MD

There are no conflicts of interest for this episode.

Introduction And Recap

In this final part of the free will series, we take a look at the relationship between the concept of free will and mental health. Is free will altered in those suffering from schizophrenia? How is well-being related to free will? If mental health professionals view the universe as purely deterministic, do they provide different care to their patients? Thinking about these questions and the rise of neuroessentialism within psychiatry allows us to recognize the influence of our environment on our decision-making. Can we change our own free will? The debate is far from settled, but a belief in free will clearly affects daily life and the practice of psychiatry.

In the last episode we discussed the manipulation of a belief in free will. We then transitioned to the importance of a static or non-altered belief in free will. We will conclude this part of the larger discussion with some final studies.

To briefly review Episode 2, we adopted a definition of free will from Baumeister, R. F., Crescioni, A. W., & Alquist, J. L. (2011) which treats the concept as a blanket term including such components as self-control, planning behavior, and rational choice. In simpler terms, free will is self-regulation. In this previous episode we also discussed the evolutionary and societal value of free will before diving into the literature on belief in free will. We examined the most common tools used for assessing belief in free will as well as its benefits for racism, aggression, cheating, and job performance.

Surprisingly, we were not able to fully cover all the benefits of a belief in free will. There were a few additional studies which examined static or non-manipulated beliefs in free will. They found similar results to the previous studies.

A static belief in free will is associated with better academic performances, though belief in free will does show some variation across cultures Feldman, G., Chandrashekar, S. P., & Wong, K. F. E. (2016).

Study 1

Participants: 116 undergraduate students from the same university in Hong Kong participated for course credit (84 from Hong Kong, 16 mainland China, 16 international)

Methods: belief in free will was assessed with a single slider [0-100] with 0 being I do not have free will and 100 being I have free will.

Participants then were assessed on the number of spelling errors they were able to detect in 16 English sentences about science.

“Task performance was measured using two indices, namely, the number of spelling mistakes detected and a time measure calculated by a log transformation of the average time spent on the task divided by the number of spelling mistakes correctly identified”

Results: “The relationship between the belief in free will and spell-checking performance was significant. Participants who reported a stronger belief in free will correctly identified more spelling mistakes (r = .20, p = .033) and did so in less time (r = −.20, p = .029).”

“Multiple-regression analyses showed similar results for the number of correctly identified mistakes after controlling for age, gender, and country of origin (β = .20, ΔR2 = .04, p = .032; F(5, 109) = 2.89, p = .017), and slightly weaker results for time (β = −.17, ΔR2 = .03, p = .077; F(5, 109) = 2.44, p = .039).”

Study 2

Participants: 614 undergraduate students from a university in Hong Kong participated for course credit. All students took the same core course using similar syllabuses, but it was taught by 5 different professors in 10 different sections.

Methods: The GPAs for the 518 participants who completed the course were obtained. belief in free will was measured using the free will subscale of the FAD scale. Assessment of implicit theories on capacity for change was also assessed using 8 items and a likert scale [1-6]. Self control was measured through the Self-Control Scale (SCS), and overall performance for the class was standardized within each of the 10 class sections.

Results: “The belief in free will exhibited a positive correlation with the final course grade (N = 614; r = .08, p = .043) and a similar effect for the overall GPA of the semester (N = 518; r = .09, p = .035).”

“The belief in free will was positively correlated with trait self-control (r = .19, p < .001) and negatively correlated with implicit theories (general: r = −.12, p = .004; intelligence: r = −.24, p < .001).”

A static disbelief in free will is associated with reduced helping behavior Baumeister R. F., Masicampo E. J., Dewall C. N. (2009)

Results: 52 undergraduate students were recruited for partial course credit

Methods: belief in free will was measured with FAD and an emotional check was conducted with PANAS.

Participants were then exposed to a seemingly random radio interview in which a college student described the recent death of her parents and her need to drop out of school to care for her siblings. Each participant was then given a flyer describing how they could help the student they heard about. Participants then ranked how many hours they would be willing to donate to help her.

Results: “Belief in free will was positively associated with helping behavior. Results showed that disbelief in free will predicted a lower number of hours for which participants volunteered, β = –.30, t = –2.24, p < .03. Treating helping as a dichotomous measure yielded similar results. Disbelief in free will was associated with a lower tendency to volunteer any help at all, B = –.15, SE = .07, Wald = 4.95, p < .03. These findings suggest that chronic disbelief in free will relates to a lower likelihood of helping another person” (265).

Free Will And Mental Health

How do free will and mental health interact? Any interaction between free will, belief in free will, and mental health is not as easily tested or readily published, but some connections do exist. At the outset, it is important to distinguish free will from other terms common to psychiatry and mental health. Psychiatrists are often asked to determine decision-making capacity, however; conflating it with free will can lead to a determination that those suffering from schizophrenia or severe depression would not only lack decision-making capacity, but also free will. Renato Ramos takes this concept one step further by explicitly arguing for the free will of schizophrenic patients through the use of self-organized criticality. Ramos is further supported by Willem Martens who uses a more traditional approach to the concept of free will to claim that psychosis is not always incompatible with free will.

DMC is often defined as the ability to express a choice, understand information, appreciate personal relevance, and reason logically.

Schizophrenia or severe depression can alter the ability to express a choice or understand the personal relevance of information. These pathologies can also alter the perception of self to such an extent that the individual feels no continuity with their former desires and is unable to express long-held beliefs. These changes do make DMC very challenging. However, being a “different person” does not necessarily violate free will.

If an individual inherits an entirely new set of desires or changes the priority they ascribe to certain motivations, they are not precluded from understanding and acting on these desires. They still possess free will even though they lack DMC for any useful decisions.

Viewing free will as Self-organized criticality Ramos, R. T. (2011)

Self-organized criticality (SOC) is explained by mathematical power laws explaining “the nonrandom variation of a given event over space or time” (38).

A common example is adding grains of sand to a pile of sand. The movement of each grain cannot be predicted, but the overall movement of the pile to maintain a given slope through avalanches is predictable. The only requirement is that each grain must not have restrictions on its placement.

Systems with SOC also have self-similarity within each object. “Self-similarity in terms of human behavior means that although very agitated individuals show intense variations in their behavior (in terms of social interactions, for example) in comparison with depressive individuals (who are less socially interactive in absolute terms), the probability of observing small or bigger variations of their behavior in relation to their basal levels is the same” (39).

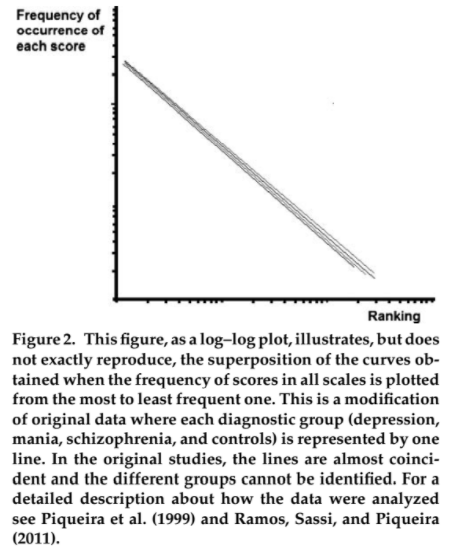

This concept is supported by a study of 40 inpatient psychiatric patients (19 MDE, 11 mania, 10 schizophrenia) and 34 “normal individuals.” Psychiatric patients were rated on a scale of 1-5 for psychomotor activity, and the control subjects used a 1-5 self-rating scale for well-being.

“Even exhibiting different absolute values, the curves obtained from each group, expressing their behavioral variability in percentage in relation to themselves, can be superimposed over the curves obtained for all other groups” (39).

“The emergence of SOC does not depend on any external or centralized control, and therefore my proposal is that the free expression of desires, judgments, and decisions about how to behave is sufficient to generate such patterns” (39).

“I briefly presented these psychopathological concepts to argue that the expression of what we call free will can exhibit intense variations in different conditions and even in the same individual in different epochs” (40).

MH: This idea of free will being preserved despite significant changes in the individual plays an important role in the idea that free will can coexist with severe mental health disorders.

An SOC model of human interaction gives “heuristic value” since it allows for an understanding of how local interactions can shape an entire social system. An SOC model also relies on “the presence of relative individual freedom” in order to function (42).

“Considering that I feel these different versions of myself as still “me,” I can describe free will as the cognitive experience of having made an autonomous decision despite not being fully aware of all interactions between my brain–mind process and the external information necessary for an adequate contextualization of this action” (42).

Free will is not categorically incompatible with psychosis Martens, W. H. (2007)

“To have free will is to have what it takes to act freely. When an agent acts freely -- when she exercises her free will -- what she does is up to her. She is an ultimate source or origin of her action”

Martens believes different psychoses can be functional in their fulfillment of internal needs to survive, belong, have power, have freedom, and to change or transform.

Survive: psychosis for coping with unbearable circumstances

Belong: erotomania used to fulfill this need

Power: grandiose delusions increase power perception

Freedom: a break from obligations

Transform: higher openness to feedback associated with greater delusion proneness

Martens also believes that a narrowly defined set of psychotic patients may qualify as having free will when they are motivated to change, have insight, mild symptoms, self-correction, coping skills, obtain effective therapy, experience optimal support, and have low limited life stress

MH: This description of the relationship between free will and psychosis links symptom severity to the potential to free will. This linkage is not necessary, but it does demonstrate that a more limited definition of free will can also coexist with psychosis.

Health care providers should then work to move patients toward the criteria listed above

“In order to increase free choice the patients must learn to cope with adverse conditions and circumstances that easily interfere with it”

MH: I would argue that making a better decision does not necessarily mean free will has been altered. free will says nothing of the quality of a decision, though improved decision-making ability is an obviously good goal.

Additional Benefits Of A Belief In Free Will

Free will also relates to mental health in a broader way since it promotes meaning in life, true self-knowledge, and shows some association with passionate love. Though these relationships are not as direct as a connection between belief in free will and depression, they still provide useful examples and an opportunity for further research.

Self-Regulation can be seen as a link between free will and Meaning in Life Van Tongeren, D. R., DeWall, C. N., Green, J. D., Cairo, A. H., Davis, D. E., & Hook, J. N. (2018)

Previous definitions of free will include self-regulation as a key social benefit, philosophical construct, and physiologic mechanism of free will. The link between self-regulation and meaning in life can then be used to connect free will or belief in free will with mental health.

Authors provide a theoretical model for the meaning-making process

1) “People adopt cultural standards for what makes life meaningful and are motivated to meet those standards” .

2) “They engage in monitoring processes to detect any potential feelings of meaninglessness that arise from a mismatch between their experience and standards”

3) “Finally, people must have the strength to reaffirm a sense of meaning following threats or feelings of meaninglessness by enacting specific behaviors”

Authors additionally posit self-regulation as a mechanism for obtaining coherence (sense-making), significance (belonging), and purpose (goal pursuit).

Lower belief in free will decreases true self-knowledge, but a link between lower self-knowledge and lower feelings of self-authenticity was not established. Seto, E., & Hicks, J. A. (2016)

“According to many theorists, people’s belief that they understand who they really are is related to psychological health and well-being (e.g., Rogers, 1961; see Freud, 1949, 1961, for an alternative perspective). Self-alienation refers to the extent to which one feels out of touch or disconnected with one’s true self (Costas & Fleming, 2009; Rokach, 1988; Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis, & Joseph, 2008). The experience of self-alienation is believed to evoke the feeling that one’s conscious awareness is discrepant from one’s actual experience of thoughts and emotions”

“After all, our sense of agency is believed to give rise to some of the most important aspects of the self such as personal strivings, desires, and aspirations (McAdams, 2013; McAdams & Cox, 2010; Ryan & Deci, 2006). In fact, Wegner (2003) argues that within every individual is a self-portrait that ‘‘we cause ourselves to behave,’’ and our sense of self comes from how we assign authorship or agency to our actions (p. 1)”

Study 1: Hypothesize lowering belief in free will => less self-knowledge

Participants: 304 people were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk and reimbursed $0.50 for their time

Method: Manipulation was adapted from Vohs and Schooler (2008) with a combination of pro and anti-free will passages and sentences as well as a reflection on how true each statement was in their own experience. Self-alienation was assessed on the 4-item self-alienation subscale of the Authenticity Scale while true-self awareness was based on the 12-item awareness subscale of the Authenticity Inventory.

Results: “Participants who wrote about experiences involving low belief in free will reported greater self-alienation (M = 2.59, SD = 1.35) and less true-self awareness (M = 5.09, SD = .93) than participants who wrote about experiences with high free will (M = 2.26, SD = 1.29, for self-alienation, and M = 5.38, SD = .88, for true-self awareness)” (729).

Study 2: Hypothesize lowering belief in free will => less self-knowledge => less authenticity in decision-making task

Method: Similar method to Study 1 with the addition of a decision-making task of keeping a specific amount of money for themselves or giving it to charity ($25-$2,000).

Authenticity was assessed through self-report on a 7 point scale asking about their decision as ‘‘an expression of [their] true self, or who [they] really are, ‘deep down inside,’’’ ‘‘align[ed] with [their] inner core values,’’ and ‘‘reflective of their central identity.’’ (730).

Results: No significant difference in state self-alienation t(280) = 1.598, p = .111, d = .192, 95% CI [-.066, .635] between low and high free will belief groups, but there was a trend toward significance.

“We also conducted an independent samples t-test to determine if there were differences in the perceived authenticity of participants’ decision-making behaviors. There was a significant difference in how authentic participants felt during the moral decision task, t(280) = -2.958, p = .003, d = -.353, 95% CI [-.854, -.172]”

“Participants in the low free will belief condition reported less authenticity during the decision-making task (M = 4.72, SD = 1.53) than participants in the high free will belief condition (M=5.23, SD=1.38)”.

Belief in free will and passionate love (‘‘a state of intense longing for union with another” ) are correlated, but so are a belief in determinism and passionate love with some variations across cultures. Boudesseul, J., Lantian, A., Cova, F., & Bègue, L. (2016)

Cultural conceptions of love seem to value both the free expression of love as well as its deterministic aspects where those in love cannot control their emotions or feelings (49).

“As mentioned earlier, increased belief in free will tends to make people more severe and less forgiving. Still, a recent study has shown that increased belief in free will is linked to higher commitment in relationships and, more surprisingly, to a greater willingness to forgive relationship partners for their faults (Crescioni, Baumeister, Ainsworth, Ent, & Lambert, 2015)” (50).

“Moreover, in the same way as we do not voluntarily fall in love, it also seems that we cannot stop loving a person at will. Indeed, cognitive control is impaired in the early stages of passionate love (van Steenbergen, Langeslag, Band, & Hommel, 2014). In fact, as mentioned earlier, it is not even clear that such control would be desirable. Rather, people may prefer that their partners love them because they are attracted to them, not because they are free to choose to”

Study 1

Participants: Amazon Mechanical Turk (82% India, 12% U.S.)

Methods: The Passionate Love Scale (Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986) was used to assess passionate love and the FAD-plus was used to assess belief in free will.

Results: “belief in free will was positively related with the level of passionate love, t(250) = 7.23, 95% CI [0.75, 1.31], p < 0.001, ᘉ2 = 0.173, above and beyond the level of belief in determinism and relationship status” (52).

“belief in determinism was also positively related to passionate love, t(250) = 2.23, [0.03, 0.56], p = 0.027, ᘉ2 = 0.019, controlling for belief in free will and relationship status” (52).

Study 2

Participants: Amazon Mechanical Turk (47% India, 52% U.S.)

Methods: The Passionate Love Scale (Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986) was used to assess passionate love and the Free Will Inventory was used to assess belief in free will

Results: “people with higher level of belief in free will had a higher level of passionate love, t(234) = 3.22, p = 0.001, 95% CI [0.13, 0.53], ᘉ2 = 0.042 (controlling for belief in determinism and relationship status)” (53).

“when we controlled for belief in free will and relationship status, we found a positive link between belief in determinism and passionate love, t(234) = 2.83, p = 0.005, [0.06, 0.33], ᘉ2 = 0.033” (52).

Study 3

Participants: Amazon Mechanical Turk (44% India, 56% U.S.)

Methods: The Passionate Love Scale (Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986) was used to assess passionate love and the Free Will Inventory was used to assess belief in free will

Additional questions regarding religious affiliation were added to the overall questionnaire.

Results: “In contrast with what has been observed in Study 2 and previous studies (Nadelhoffer et al., 2014), belief in free will was positively and significantly correlated with belief in determinism, r(231) = 0.14, 95% CI [0.02, 0.27], p = 0.028” (54).

“This suggests that the relationship between free will and love is stronger among Indians (simple effect, t(225) = 3.72, p < 0.001, g2 = 0.058) than among Americans (simple effect, t (225) = 1.91, p = 0.058, ᘉ2 = 0.016)” (54).

“people with a higher level of belief in free will displayed a higher level of passionate love, t(228) = 5.27, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.37, 0.81], ᘉ2 = 0.109, controlling for all other variables in the model (i.e., belief in determinism, country of residence, and the interaction between belief in free will and country of residence)” (54).

“even though the hypothesized positive relationship was observed between belief in determinism and passionate love, it failed to reach statistical significance in a statistical model controlling for all other variables, t(228) = 0.75, p = 0.45, [0.08, 0.19], ᘉ2 = 0.002” (54).

“we found an overall positive and significant association (medium effect size) between belief in free will and passionate love (r = 0.30, 95% CI [0.21, 0.40], SE = 0.05, p < 0.001), an overall positive and significant association (with a descriptively smaller effect size) between belief in determinism and passionate love (r = 0.16, [0.09, 0.23], SE = 0.04, p < 0.001),11 and a non-significant association between belief in free will and belief in determinism (r = 0.18, [0.16, 0.52], SE = 0.17, p = 0.29). This last result suggests the independence of these two constructs in our samples” (54).

Neuroessentialism And Free Will

Finally, the most significant and practical connection between free will and mental health is the concept of neuroessentialism which claims full determinism. This concept is advocated by Sam Harris, among others, and is not rare in the realm of neuroscience. Neuroessentialism has importance for both patients and physicians, giving it practical value and importance.

Neuroessentialism has become a powerful conceptual framework for patients, pharmaceutical companies, and clinicians. However, the stated benefits of this concept can be overinflated and the drawbacks can be underrepresented. Schultz, W. (2018)

“Neuroessentialism is the view that the definitive way of explaining human psychological experience is by reference to the brain and its activity from chemical, biological, and neuroscientific perspectives. . . . For instance, if someone is experiencing depression, a neuroessentialistic perspective would claim that he or she is experiencing depression because his or her brain is functioning in a certain way” (608).

“The biological approach is hypothesized to accomplish this [reduction of stigma] by positing that the individual is not responsible for the development of his or her psychological disorder. Instead, his or her biology is responsible (Corrigan et al., 2000)”

“Meaning, the lack of responsibility an individual might have for his or her psychological disorder when explained from a biological perspective can be “outweighed by the adverse effects mediated by perceived differentness and dangerousness, respectively” (Schomerus et al. (2014), p. 311)”

MH: Efforts to reduce stigma should be praised, but they should also be critically analyzed to determine if they meet their goal.

“Second, there is evidence that the significant increase in direct-to consumer (DTC) advertising for antidepressants is related to rising prescription rates (Park & Grow, 2008). Such advertisements portray depression as a biological medical condition that can successfully be treated with medicine (Lacasse & Leo, 2005; Leo & Lacasse, 2008)” (613).

“As such, it is not entirely surprising that psychiatric medication sales are worth tens of billions of dollars annually—$70 billion in 2010 (Hyman, 2012)” (614).

“The explanation for these increases [depression and use of antidepressants after the 2008 recession] is unlikely to be a spontaneous, unpredictable spike in brain diseases. Instead, it is likely explained by individuals whose life circumstances have taken a turn for the worse via decreased wealth, unemployment, and other difficulties (McInerney et al., 2013)”

MH: A purely biological explanation can also have the unintended side-effect of making psychiatric medications easier to sell to consumers.

“So to be us ultimately is to be physically based or realized. This does not mean, however, that each and every activity, state, aspect or component of us can be exhaustively or completely described in lower level physical scientific terms. (Graham (2013), p. 87)”

“That is, physicists studying a dollar will not find particles that defy the laws of physics, but they also will not find the dollar’s market value” (615).

“However, Beauregard argued that evidence from a variety of directions— such as the power of placebo, hypnosis, and neurofeedback—“show us very different models of what is real and what is possible than materialist science permits” (Beauregard (2012), p. 15)”

Within the same article, the authors analyzed a study on the effects of biological or psychosocial explanations of mental health pathologies patients. Following this study, an additional analysis is included on the impact of biological or psychosocial explanations for clinicians.

“Regression analyses found that “biochemical/genetic attribution scores were a significant predictor of longer expected symptoms duration and lower perceived odds of recovery” (Lebowitz et al., 2013, p. 523). Importantly, Lebowitz et al. (2013) also found that the malleability condition was effective in reducing prognostic pessimism as well as in increasing optimistic thinking and personal agency in relationship to mood. The authors concluded that “given the increasing prevalence of biomedical conceptualizations of depression, the notion that depressed individuals who hold such beliefs might be more vulnerable to pessimism about the course of their disorder is alarming” (p. 525)”

Depressed individuals with biochemical understandings of their disease believe they will suffer from the disease for longer than their psychosocial counterparts. Lebowitz, M. S., Ahn, W. K., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2013).

Participants: Adults recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk were included after completing the Beck Depression Inventory-II and scoring ≥ 16. N=108.

Method: Questionnaire contained 10 potential causes for depression which participants rated on a scale [1-7]. After rating causes, participants used the same scale [1-7] to rate how long they felt they would remain depressed.

Results: “Biochemical/genetic attributions significantly predicted higher scores on the symptom duration scale in both Study 1a, β=.23, p=.02, and Study 1b, β=.42, p<.01. (Because of the symptom-duration measure’s ordinal nature, we also confirmed these results using ordinal regressions, p=.01 in Study 1a, p=.02 in Study 1b.)”

Clinicians believe psychotherapy to be less effective when shown biological descriptions of mental health pathologies. Lebowitz, M. S., & Ahn, W. K. (2014).

Participants: Mental health clinicians[psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers] (Study 1 n=132, Study 2 n=105)

Method: Participants read vignettes describing patients with schizophrenia and social phobia (study 1) or major depression and OCD (study 2). Each disorder has two explanatory passages (biological and psychosocial). Each explanation was paired with one of the two patient vignettes.

Participants then read a list of 18 adjectives to rate their feelings toward the vignette patients (a validated measure of empathy).

Participants also rated to what extent “they believed each patient’s symptoms could improve with medication and with psychotherapy . . . and the clinical utility . . . of each biological and psychosocial explanatory passage”

Results: “Across disorders, the biological explanation yielded significantly less empathy than the psychosocial explanation, both in study 1 [F(1,122) = 32.66, P < 0.001] and study 2 [F(1,103) = 18.16, P < 0.001]”

“we reran these ANOVAs with an additional variable distinguishing medical doctors (MDs) from nonMDs, and found that MDs reported significantly less empathy overall than non-MDs. More importantly, in both studies, the biological explanations yielded less empathy than the psychosocial explanations among both MDs and non-MDs”

“in study 1, clinical utility scores showed a two-way interaction [F(1,122) = 10.11, P < 0.01]; no significant difference emerged for schizophrenia, but the biological explanation was rated as less useful in the case of social phobia [t(123) = −3.15, P < 0.01]. In study 2, the biological explanations yielded lower clinical utility scores across disorders [F(1,104) = 19.98, P < 0.001] (Fig. 2). In both studies, there were no significant differences in clinical utility ratings between MDs and non-MDs or significant training (MD vs. non-MD) by explanation interactions”

“Across disorders in both studies, clinicians perceived psychotherapy to be significantly less effective when symptoms were explained biologically rather than psychologically (all t > 2.00, all P < 0.05)”

“For all disorders except schizophrenia,biological explanations yielded significantly higher medication effectiveness ratings than did psychosocial explanations (all t > 3.87, all P < 0.001)”

“In addition to client expectancies, clinician expectancies for client improvement also have a significant impact on treatment outcomes and, thus, conceptualizations of depression that decrease clinician expectancies will likely worsen treatment outcomes (Byrne, Sullivan, & Elsom, 2006; Meyer et al., 2002)”

The diminished importance of psychotherapy among mental health professionals ascribing to the concept of neuroessentialism is doubly harmful when considering the multiple contexts in which psychotherapy matches or outperforms pharmaceutical interventions.

A review of meta-analyses on the efficacy of CBT shows some advantages for CBT over pharmacotherapy. Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J., Sawyer, A. T., & Fang, A. (2012)

“CBT is arguably the most widely studied form of psychotherapy. We identified 269 meta-analytic reviews that examined CBT for a variety of problems, including substance use disorder, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, depression and dysthymia, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, somatoform disorders, eating disorders, insomnia, personality disorders, anger and aggression, criminal behaviors, general stress, distress due to general medical conditions, chronic pain and fatigue, distress related to pregnancy complications and female hormonal conditions” (434-435).

“Similarly, the efficacy of CBT for bipolar disorder was small to medium in the short-term in comparison to treatment as usual. However, there was limited evidence for the superiority of CBT alone over pharmacological approaches; for the treatment of depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder, the use of CBT was well supported. However, the long-term superiority compared to other treatments is still uncertain” (435).

“Compared to pharmacological approaches, CBT and medication treatments had similar effects on chronic depressive symptoms, with effect sizes in the medium-large range (Vos et al. 2004). Other studies indicated that pharmacotherapy could be a useful addition to CBT; specifically, combination therapy of CBT with pharmacotherapy was more effective in comparison to CBT alone (Chan 2006)” (430).

“CBT for social anxiety disorder evidenced a medium to large effect size at immediate post-treatment as compared to control or waitlist treatments, with significant maintenance and even improvement of gains at follow-up (Gil et al. 2001). Further, exposure, cognitive restructuring, social skills training and both group/individual formats were equally efficacious (Powers et al. 2008a), with superior performance over psychopharmacology in the long term (Fedoroff and Taylor 2001)” (430).

“In comparing relative efficacy of CBT versus pharmacotherapy, effect sizes were large on body dysmorphic disorder severity measures for CBT, and ranged from medium to large for pharmacotherapy (Williams et al. 2006)” (431).

“For binge eating disorder, a recent meta-analysis found that psychotherapy and structured self-help yielded large effect sizes, when compared to pharmacotherapy, which yielded medium effect sizes (Vocks et al. 2010)” (431).

Practical Free Will And A Spectrum Approach

How should patients be counseled and free will approached in the clinic? What affects free will itself? Can it be improved or better exercised based on the influence of the environment, thought content, or traditional concepts like “will power”?

Free will may have a physical component according to Glannon, W. (2011), but we believe a physical definition of free will may only muddy the waters. free will is affected differently by different pathologies.

“Free will consists in the ability to initiate and execute plans of action” (15).

Response: Does someone who is simply weaker than average also have decreased free will because they cannot carry out every day tasks?

Author claims free will exists along a spectrum and can be enhanced (15).

“We choose and act freely in the absence of coercion, compulsion, and constraint. This requires the mental capacity to respond to reasons for or against certain actions and the physical capacity to act or refrain from acting in accord with these reasons” (15-16).

Response: This definition of free will seems impossible. Which human being acts with no constraint at any time in their life? The incorporation of a physical requirement seems unnecessary.

Glannon uses Parkinson’s as an example of decreased free will where a patient may be able to consent to deep brain stimulation while also being unable to control tremors, “while one aspect of the will is impaired, another aspect may be intact” (16).

Response: Is the will not purely mental by definition? Adding a physical component of will is unnecessarily complicated.

Glannon believes OCD can limit free will (16).

Response: I would propose that OCD may limit the expression or acts of a free will, but not free will itself.

Glannon states that acts of suicide commited by one suffering from depression are not free acts and therefore justify “third-party intervention to prevent an attempted suicide” (17).

Response: Does free will necessitate “good” or rational decisions? Can decision-making capacity be defined separately from free will?

“This occurred in the case of a teacher in Virginia who uncharacteristically began displaying pedophilia associated with a meningioma pressing on his right orbitofrontal cortex. Removal of the tumor resolved the pedophilia. This behavior returned with the growth of a new meningioma in the same brain region and resolved again when the second tumor was removed (Burns and Swerdlaw 2003; Bechara and Vander Linden 2005)” (17).

Glannon believes this evidence is not strong enough to determine causality and later notes that the presence of impulses does not mean self-control is impossible (18).

“Bernadette McSherry argues that there is no objectively verifiable test determining that an accused individual could not control him or herself or that he or she merely would not (McSherry2004).Robert Sapolsky further notes difficulties associated with “distinguishing between an irresistible impulse and one that is to any extent resistible but which was not resisted” (Sapolsky 2004, 1790)”

“The neurobiology of addiction imposes mental constraints on the reasoning and decision making that are necessary for a person to control his or her behavior and thus retain free will. Changes in addicts’ brains from repeatedly taking a drug may compromise these cognitive capacities to such a degree that the addict cannot choose and act freely. The desires resulting from these changes compel the addict to continue taking a drug” (18).

Response: Is it therapeutically helpful to tell an addict they lack free will? If the addict remains internally conflicted about using drugs, is this conflict evidence of free will?

DJP: There are opponents of the biological determinism in regards to addiction. Dodes argues against the biological aspect in favor of a moment of feeling out of control, when deciding to use, immediately (without the substance) brings someone into a state of calm.

“Genetic and social factors may predispose them to this behavior and make them more vulnerable to addiction. But predisposition is not compulsion. These factors alone will not cause one to take a drug that results in an addiction. Even if addictions undermine voluntary choice once the underlying brain dysfunction becomes chronic, the initial phase of taking drugs can be voluntary” (19).

“If their initial choices are informed and free, then their responsibility transfers from the earlier to the later time, even if they cannot act freely at that time” (20).

Response: Glannon appears to be conflating informed consent with free will.

Psychopathy:

“Also, given that psychopaths identify their victims as people they can harm and know that they do harm them, they seem to have some capacity to respond to moral reasons and be at least partly morally responsible for their actions” (21).

“In exploiting others and disregarding their rights and interests, psychopaths know that their actions are wrong; but they do not care (Cima, Tonnaer, and Hauser 2010).”

DJP: They have motivations that seem to align with their choices, more power, more sexual gratification… also the desire to not be caught plays a huge role

The article ends with a discussion of free will enhancement through the use of drugs which either increase perception of choice or “increase the content of responsibility” such as giving a surgeon the ability to focus on and endure longer surgeries (24). This argument seems to confuse capacity with free will.

Extreme Cases (Schizophrenia, Developmental abnormality, Coma)

Self-regulation, logic, etc. can be improved. Schizophrenia and other extreme cases can be seen as having free will based on limited definitions as seen in self-organizing criticality. However, it is clear that these individuals experience a different form of free will than others.

Conclusion

After this long series, what have we gained? Hopefully, we have provided a helpful context for the entire free will discussion. More importantly, we hope we have provided evidence of the value of a belief in free will for both individuals and society. We also hope to have entered the neuroscience debate by engaging with Sam Harris’s works on free will. Finally, we hope to have provided practical examples of how a belief in free will can affect mental healthcare through the concept of neuroessentialism or assumptions that certain pathologies violate the potential for free will.

We have broadly summarized free will as self-regulation and given evidence that a belief in free will can be altered. However, making alterations in free will itself is a much more philosophical topic with more limited data. The existence of free will has not been proven, but we also believe it has not been disproven as some claim.

Moving forward it is important to acknowledge the influence of our environment and the potential for improving our decision-making processes. Better decisions are an obviously good goal, but the better choices do not necessarily mean free will itself has been influenced.

How does free will apply in today’s culture? We have given some examples of incel culture, suffering during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the hope for improving individuals and our relationships with those who are different from us in some way. There are many more applications, and we hope you’ll share your discoveries with us.