Episode 201: Psychotic Depression with Dr. Cummings

By listening to this episode, you can earn 1.25 Psychiatry CME Credits.

Other Places to listen: iTunes, Spotify

Article Authors: Cara Jacobson, James Swanson, David Puder, MD

There are no conflicts of interest for this episode.

Introduction

The underreporting of psychotic symptoms by patients in depression is a significant concern, frequently driven by the fear of consequences like hospitalization or the stigma of embarrassment.

We'll discuss the history, the differential to consider when thinking of psychotic depression, mechanisms, and treatment. Notably, individuals with psychotic depression face a suicide rate double that of their non-psychotic counterparts. A recent cohort study by Paljärvi in 2023 revealed a stark contrast: deaths due to suicide were 2.6% in the psychotic depression cohort, compared to 1% in the non-psychotic group. Alarmingly, most suicides occurred within the first two years following diagnosis. People who suffer from psychotic depression often do not report their psychotic symptoms, leading to inadequate response to normal depression treatments. With 6-25% of individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) exhibiting psychotic features, it is imperative to understand and address these unique challenges. Join us as we unravel the complexities of this underrecognized aspect of mental health.

Background

History

The concept of psychotic depression has evolved substantially over time, as shown in Table 1, thus it is vital to consider the specific diagnostic criteria and definitions used when interpreting the findings of psychotic depression research over the years.

Note. Adapted from “Psychotic Depression: Diagnosis, Differential Diagnosis, and Treatment,” by S. L. Dubovsky, B.M. Ghosh, J.C. Serotte, and V. Cranwell, 2021, Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 90(3), p. 160–177. (https://doi.org/10.1159/000511348). Copyright 2020 by S. Karger AG, Basel.

When psychotic depression is conceptualized simply as a severe form of major depressive disorder (MDD), it implies that these patients “may simply require more of the same treatment as other presentations, rather than a different therapeutic approach required by a distinct illness” (Dubovsky et al., 2021). However, we now know that depressed patients with psychotic symptoms require different treatment than those with non-psychotic depression.

Severity

While psychotic depression was once considered a manifestation only of severe major depression, more recently psychosis is not linked diagnostically to severity of depression. The psychosis itself can vary from severe hallucinations and delusions to only mild and fleeting symptoms, and the clinician should consider this when considering treatment priorities. From reviewing various studies it does seem that patients with depression and psychosis tend to have higher scores in the HAM-D or other depression rating scales. Epigenetic changes resulting from primary mood disorders are thought to decrease the threshold for expression of psychosis at a certain level of mood disorder severity in a given patient (Crow, 2007; Dubovsky et al., 2021).

Prevalence

While psychotic depression is often thought to be rare, it is, in fact, relatively common and is largely underrecognized and undertreated. In adults with major depressive disorder (MDD), approximately 6-25% have MDD with psychotic features (Coryell et al., 1984; Gaudiano et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 1991).

According to Dubovsky et al. (2021), an estimated 9-35% of children and 5-11% of adolescents report experiencing hallucinations. However, it can be difficult to interpret psychotic symptoms in children due to their developmental ability to understand fantasy vs. reality, and 75-90% of these experiences in children are transient. Still, there is evidence that psychotic experiences in childhood are associated with increased risk of mood or psychotic disorder. Additionally, psychosis in adolescents can, at times, be part of a larger picture of borderline personality disorder.

Subclinical psychotic experiences also occur in around 7% of the general population, and these are transient in 80% of cases, with 20% experiencing persistent psychotic experiences, 7% ultimately developing a psychotic disorder, and less than 1% transitioning to a psychotic disorder each year (van Os & Reininghaus, 2016). Paranoia, hallucinations, and bizarre experiences are less common in people without psychiatric illness and may indicate more clinically relevant psychosis, whereas paranormal beliefs or magical thinking without functional impairment are more often experienced in the general population (Hinterbuchinger et al., 2023; Yung & Lin, 2016).

Psychosis as a Transdiagnostic Trait

Studies examining birth cohorts and family histories of patients with mental illness suggest that psychosis is present in a wide variety of psychiatric disorders, and transmission of this trait to offspring can be independent of other features of mental illness, such as mood dysregulation or impairment of information processing, which, for example, might characterize schizophrenia (Dubovsky et al., 2021; van Os & Reininghaus, 2016).

Diagnosis

Treatment-Resistant Depression

First, it is important to clarify the meaning of treatment resistance versus pseudo resistance:

Treatment resistance refers to depression that does not respond to standard treatment.

Pseudo resistance refers to instances where either the diagnosis is incorrect or treatment was improperly carried out. For example, this may occur due to subtherapeutic medication dosing, non-compliance, malingering, unrecognized psychosocial factors contributing to depression, unrecognized somatic or psychiatric comorbidity, or drug-induced depression (Bschor et al., 2014).

For patients who do not respond as expected to prescribed medication, when possible, clinicians should ascertain whether their serum drug levels are within the therapeutic range or if they picked up the medications from the pharmacy. A history, physical and screening questionnaires (like the Epworth Sleepiness Scale) can guide the selection of tests such as: sleep study, thyroid function, ECG, syphilis serology, vitamin B12 and folic acid levels, urinalysis, EEG, HIV antibody testing. These investigations play a pivotal role in identifying any underlying conditions that may impact the patient’s symptoms or efficacy of the prescribed treatment.

Psychotic Depression as a Cause of Treatment Resistance

Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) stands as a multiphase landmark study, offering compelling evidence supporting the use of antidepressants in treating major depressive disorder. The findings indicate that approximately one in three individuals with MDD who undergo initial SSRI treatment may experience complete remission within three months (Howland, 2008).

In 2011, Dr. Roy Perlis and his team presented insights suggesting that the STAR*D trial likely included patients exhibiting psychotic symptoms alongside their MDD. This led to the observation that the effectiveness of SSRIs diminishes in those with psychotic-like symptoms (Perlis et al., 2011). Such revelations by Perlis underscore the limitation of older MDD treatment paradigms, especially in cases where psychotic features are present.

Additionally, Huang et al. (2023) found that various factors were associated with treatment-resistant depression, including mood-incongruent psychotic symptoms, which they termed “emotionally incoherent psychotic symptoms.”

When depressed patients do not improve with antidepressant treatment, clinicians should evaluate carefully for symptoms of psychosis, as misdiagnosis can be a cause of treatment-resistant depression. Patients may minimize or fail to report symptoms like delusions and hallucinations for various reasons, including deficits in abstract thinking, not recognizing their symptoms as abnormal, or fear of potential consequences of reporting symptoms, such as hospitalization or embarrassment. This may necessitate asking specific questions about delusions or hallucinations followed by further questioning to clarify the patient’s true experiences, rather than broad or general questions like simply asking if a patient sees or hears things that others do not (Dubovsky et al., 2021).

Table 2 includes some common clues that a patient may truly have psychosis, despite initially denying psychotic symptoms.

Note. From “Psychotic Depression: Diagnosis, Differential Diagnosis, and Treatment,” by S. L. Dubovsky, B.M. Ghosh, J.C. Serotte, and V. Cranwell, 2021, Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 90(3), p. 160–177. (https://doi.org/10.1159/000511348). Copyright 2020 by S. Karger AG, Basel.

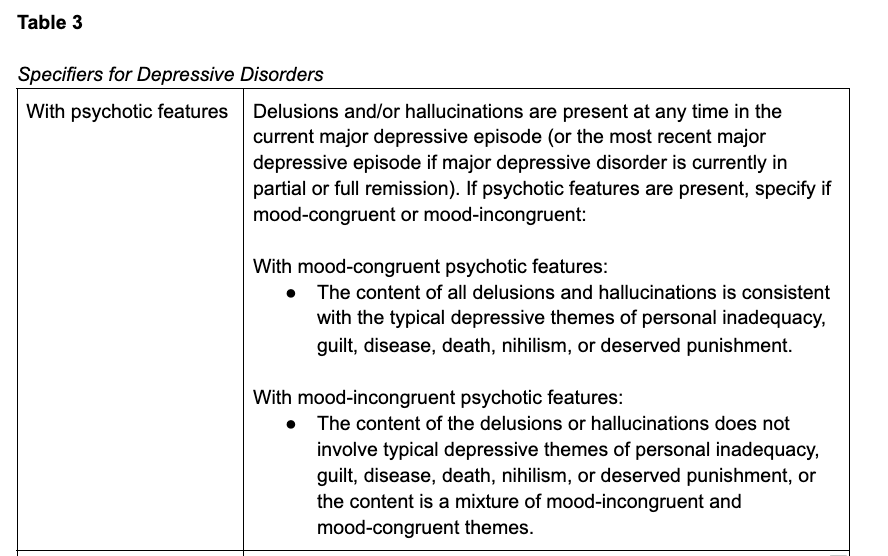

DSM 5-TR

Whereas previous iterations of the DSM defined psychotic depression only in relation with severe major depression, the current version, DSM-5-TR instead includes specifiers (Table 3) that can be applied to any depressive disorder, including conditions with milder symptoms like persistent depressive disorder, which was previously called dysthymia (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). When using the specifier, “with psychotic features,” the clinician should specify whether the psychotic symptoms are mood-congruent or mood-incongruent. Although some have posited that the prognosis for depression with mood incongruent psychotic features is worse than depression with mood congruent symptoms, most evidence indicates no difference in outcomes. However, mood-incongruent delusions do seem to be more highly associated with bipolar disorder than mood-congruent symptoms (Carlson, 2013; Domschke, 2013).

Note. Adapted from “Depressive Disorders,” by American Psychiatric Association, 2022, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). (https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787.x04_Depressive_Disorders). Copyright 2022 by American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

Differential Diagnosis

Bipolar Disorder and Depression with Mixed Features

Similar to the need to evaluate treatment-unresponsive depressed patients for signs of psychosis, clinicians should assess for the presence of hypomanic or manic symptoms, which may indicate bipolar disorder or depression with mixed features, as these conditions may require different treatment (McIntyre et al., 2016; Stahl et al., 2017).

Psychotic depression, and mood-incongruent delusions in particular, seems to increase the likelihood of bipolar disorder (Carlson, 2013; Domschke, 2013). Family history of bipolar disorder is also associated with higher rates of psychotic depression, and family history of psychotic depression is associated with increased rates of bipolar disorder compared to family history of nonpsychotic depression (Domschke, 2013).

Interestingly, mixed features such as increased energy and elevated mood in bipolar psychotic depression can mask the symptoms of depression, and cause patients with psychotic symptoms, in particular, to appear “to function at a higher level than would be predicted by the degree of symptomatology” (Dubovsky et al., 2021). This can lead clinicians to overlook the diagnosis of psychotic depression. Instead, they may dismiss patient-reported symptoms as exaggeration or evidence of a personality disorder.

Compared to unipolar depression, bipolar psychotic depression is also more frequently associated with non-auditory hallucinations, in particular visual hallucinations, though olfactory and haptic hallucinations (the sensation of being touched or having physical contact with an imaginary object or being) also occur (Baethge et al., 2005).

Children and Adolescents

Dubovsky et al. (2021) report that young patients who have depression associated with any psychotic symptoms are more likely to develop bipolar disorder than those with nonpsychotic depression. In patients with psychotic mood disorders, youth are more likely than adults to experience hallucinations, which affect 80% of children and adolescents with psychotic depression. “Auditory hallucinations are most common, but they are often accompanied by visual, olfactory, and/or haptic hallucinations” (Carlson, 2013; Sikich, 2013).

Delusions are less common in young patients with psychotic depression, affecting 22%, and delusions of reference, mind reading, and thought broadcasting are most common (Ulloa et al., 2000). As with adults experiencing psychotic symptoms, children may be hesitant to report symptoms like delusions due to fear of negative consequences, such as punishment (Dubovsky et al., 2021).

PTSD and Trauma

Some have also speculated that certain patients with apparently treatment-resistant psychotic depression may, in fact, have unrecognized PTSD (Zimmerman & Mattia, 1999). Co-morbid post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as history of childhood trauma are more common in populations with psychotic depression than those with non-psychotic depression, and psychotic symptoms are common in patients with PTSD (Gaudiano & Zimmerman, 2010; Zimmerman & Mattia, 1999). In patients with trauma histories, careful assessment is needed to differentiate between dissociative and psychotic symptoms to prevent overdiagnosis of psychosis.

Although the relationships between PTSD, trauma, borderline personality disorder, and psychotic symptoms are complicated, a 2010 study by Gaudiano & Zimmerman found increased rates of childhood trauma and comorbid PTSD in patients with psychotic major depressive disorder (MDD) compared to those with nonpsychotic MDD, but there was not a statistically significant difference in rates of borderline personality disorder (BPD) between patients with psychotic and nonpsychotic MDD, suggesting that BPD is equally prevalent in each group. Therefore, an individual patient with psychotic depression may have both PTSD and borderline personality disorder.

It can be difficult to distinguish between psychotic depression and PTSD with psychotic features, though delusions and hallucinations unrelated to trauma in patients with PTSD may reflect comorbid psychotic depression rather than a feature of their PTSD (Hamner et al., 1999). While there is limited evidence on the efficacy of either antipsychotic medications or psychotherapy in PTSD with psychosis, these treatments may be beneficial (Buck et al., 2019; Cheng et al., 2019; Compean & Hamner, 2019). However, we do not know if patients with psychotic depression require different approaches to treatment depending on whether or not they have a history of significant trauma or posttraumatic symptoms (Dubovsky et al., 2021).

Additionally, psychotic symptoms directly related to past traumatic experiences, also called trauma-congruent psychotic symptoms, may represent aspects of trauma like flashbacks or dissociative re-experiencing, rather than “true” psychosis, though not all clinicians agree with this idea, and empirical evidence is limited (Clifford et al., 2018; Dubovsky et al., 2021; Piesse et al., 2023; Tschöke & Kratzer, 2023). It is unclear whether treatment needs or prognosis differ between depressed patients with trauma-congruent psychotic symptoms and mood-congruent psychosis symptoms (Dubovsky et al., 2021).

Borderline Personality Disorder

Similar to those with PTSD, patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) can experience psychosis, either associated with the BPD itself or due to a comorbid condition such as MDD with psychosis. It can also be challenging to differentiate BPD from primary psychotic disorders, especially as both typically first emerge during adolescence and young adulthood. However, BPD is not associated with the disorganization or negative symptoms seen in schizophrenia, and voices heard by patients with BPD tend to be more critical, distressing, and abusive (Cavelti et al., 2021). Belohradova et al. (2022) also highlight the similarities between psychotic symptoms in BPD and schizophrenia, in addition to advocating against dismissing these symptoms in patients with BPD as not serious.

Psychotic symptoms are common in BPD, occurring in around a quarter of these patients (Belohradova et al., 2022). Auditory hallucinations and persecutory delusions are the most frequent psychotic symptoms in BPD, and these are closely associated with or worsened by specific situations, especially interpersonal stressors (D'Agostino et al., 2019). Loneliness or feelings of social isolation are significant factors influencing hallucinations in these patients (Belohradova et al., 2022). Notably, hallucinations in patients with BPD are linked to more frequent hospitalization and increased suicidal risk (Slotema et al., 2018). Future research should focus on the quality and context of psychotic symptoms in BPD and explore links with traumatic experiences, emotion dysregulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal sensitivity (D'Agostino et al., 2019; Cavelti et al., 2021).

Schizophrenia and Primary Psychotic Disorders

Depressive episodes occur in approximately 27-48% of patients with schizophrenia, though depression can be difficult to differentiate from negative symptoms or antipsychotic side effects like bradykinesia, affective blunting, or dysphoria (Dubovsky et al., 2021). However, depressed mood, pessimism, and suicidality are more indicative of depression, while blunted affect and alogia are more suggestive of negative symptoms (Krynicki et al., 2018). Still, antidepressants may lead to improvement of negative symptoms in these patients, though the evidence is limited (Dubovsky et al., 2021).

It is important to avoid increasing antipsychotic doses beyond the point of futility, as these medications are dopamine antagonists and can cause patients to become anergic, anhedonic, or withdrawn due to excessive dopamine blockade, mimicking either negative symptoms or depression. While it was previously thought that initially using higher antipsychotic doses would treat psychosis more quickly or more effectively, this theory of rapid neuroleptization has largely been discredited.

Above the therapeutic range for medications like olanzapine the receptor occupancy curve flattens out, meaning that large increases in medication dosage would be required even to slightly increase the percentage of receptors that are occupied at the risk of substantially worsening the side-effect burden, but with minimal additional benefit from the medication. Clinicians should monitor blood levels to ensure that patients are not overmedicated. For more information on antipsychotic plasma levels, see Episode 127.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

As many patients have both obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and major depression, Rothschild et al. (2006) note the importance of distinguishing the obsessions, intrusive thoughts, and ruminative thoughts of OCD from true delusions that might instead suggest a diagnosis of psychotic depression. The comorbidity of OCD and schizophrenia and the concept of a schizo-obsessive spectrum have also been increasingly recognized in recent years (Cavaco & Ribeiro, 2023).

Substance-Induced Psychosis

Various substances of abuse can induce psychosis, including cocaine, cannabis, synthetic cannabinoids (like spice or K2), synthetic cathinones (bath salts), hallucinogens (psychedelics), entactogens (like MDMA, also known as ecstasy), phencyclidine (PCP), ketamine, and methamphetamines (Fiorentini et al., 2021). For example, around one third of people abusing methamphetamine have experienced methamphetamine-induced psychotic disorder (Fiorentini et al., 2021). Often, substance-induced psychotic symptoms are transient and will resolve after abstinence from the substance; however, several drugs–including cannabis and methamphetamine–are associated with more persistent psychosis or conversion to a chronic psychotic disorder, such as schizophrenia (Fiorentini et al., 2021).

Substance-induced psychosis, particularly related to amphetamine use, should be considered in any patient with a combination of psychosis, hypertension, and tachycardia (Mullen et al., 2023). In addition to psychiatric symptoms like paranoid delusions, hallucinations, mood lability, agitation, and suicidal or homicidal ideation, these patients may also present with a malnourished or disheveled appearance, diaphoresis, skin excoriations due to delusional parasitosis, intraoral exam findings suggestive of “meth mouth,” and abnormal movements, such as pacing or choreiform movements (Mullen et al., 2023). Patients in withdrawal from methamphetamines frequently experience dysphoria, irritability, and agitation, which is associated with alterations in brain levels of dopamine and other neurotransmitters due to the chronic neurotoxic effects of methamphetamine (Nordahl et al., 2003), and this may look like psychotic depression.

Intravenous benzodiazepines are considered first-line treatment for acute amphetamine-related psychosis, while antipsychotics can also be used if needed, and lipophilic beta-blockers (e.g., metoprolol or labetalol) can help treat agitation and hyperadrenergic vital signs in these patients (Mullen et al., 2023). ECT may also be beneficial for patients with refractory methamphetamine-induced psychosis (Grelotti et al., 2010).

The typical course involves methamphetamine inducing non-psychotic psychiatric symptoms, which progress to pre-psychotic symptoms then psychosis (Ujike & Sato, 2004). For example, a patient may develop hypervigilance which ultimately progresses to paranoia and persecutory delusions. While there is wide variability in the length of time from initial methamphetamine use to onset of psychosis (from several weeks to 20 years), a 2004 study of Japanese adults found that this occurred on average after 5.2 ± 5.9 years, and the risk of developing psychosis increased substantially with methamphetamine use longer than 6 months (Ujike & Sato, 2004). Psychotic symptoms typically resolve within one week or up to one month with abstinence from methamphetamine and beginning antipsychotic treatment, but some patients can experience psychosis lasting over 6 months, especially those with a longer history of methamphetamine abuse (Ujike & Sato, 2004). Even after recovering from methamphetamine-induced psychosis, relapse of these symptoms occurs much more quickly after repeated exposure to methamphetamine, most frequently within one month, often in less than one week, and possibly even after only a single dose of methamphetamine; this vulnerability to psychotic relapse can last years or even decades after the last use (Ujike & Sato, 2004). Additionally, long-term methamphetamine abuse can predispose patients to spontaneous relapse of psychotic symptoms in the setting of stressors such as jail detention, severe insomnia, or heavy alcohol use, even in the absence of further methamphetamine consumption (Ujike & Sato, 2004).

Delirium and Medical Causes

Clinicians must have a high index of suspicion for delirium, especially in situations with rapid onset of symptoms and fluctuating levels of arousal. This is particularly vital in hospital settings where 29-64% of general medical and geriatric inpatients may have delirium (Inouye et al., 2014). Additionally, hypoactive delirium is most common and may go unrecognized in around one third of elderly patients (Al Farsi et al., 2023). Performing a mental status exam and having patients perform clock drawing can assist with identifying delirium.

There are numerous causes of delirium, including infections (urinary tract infections, pneumonia, etc.) or post-surgical complications, sometimes relating to anesthesia effects. Once the underlying cause has been identified, it should be treated appropriately, though the delirium may persist even after discharge from the hospital (Al Farsi et al., 2023).

Interestingly, thyroid dysfunction may also be associated with psychotic depression (Peng et al., 2023).

Neurobiology of Depression

Synaptic Dysfunction and Neuronal Atrophy in Depression

Duman and Aghajanian (2012) proposed that depression may result from synaptic dysfunction, in particular, “destabilization and loss of synaptic connections in mood and emotion circuitry.”

Evidence suggests that depression is associated with loss of synapses and dysregulated connections between different brain regions, as well as neuronal atrophy in the cerebral cortex and limbic system (Duman & Aghajanian, 2012). For example, brain-imaging studies have consistently found decreased prefrontal cortex and hippocampus volumes in the brains of patients with depression (Duman & Aghajanian, 2012).

Chronic Stress

Chronic unpredictable stress, which researchers use to help model depression in experiments, causes depression-like behaviors in rodents, and chronic stress is known to result in neuronal atrophy and decreased synaptic connections (Duman & Aghajanian, 2012). Chronic stress has also been shown to decrease brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is discussed in the next section, in addition to causing neuron degeneration in the amygdala and nucleus accumbens and disrupting brain circuits in these areas that regulate emotion, motivation, and reward behaviors (Duman & Aghajanian, 2012). Some of these results from chronic stress can be reversed with antidepressant treatment, exercise, or enriched environments (Duman & Aghajanian, 2012).

BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is vital for brain development, as well as neuron function, survival, and plasticity, and alterations in BDNF have been strongly implicated in neuronal atrophy and loss of synapses (Duman & Aghajanian, 2012). Lower postmortem BDNF levels have been found in the brains of depressed patients, and exposure to either stress or glucocorticoids (corticosteroids) results in decreased BDNF expression in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Duman & Aghajanian, 2012). In contrast, chronic use of antidepressants increases expression of BDNF in these areas (Duman & Aghajanian, 2012).

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis

Disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and elevated cortisol levels, in particular, have been implicated in the pathophysiology of psychotic depression (DeBattista et al., 2006). There is some evidence that 6-7 days of treatment with mifepristone, an antagonist of the type II glucocorticoid receptor and progesterone receptor, can benefit patients with psychotic depression (DeBattista et al., 2006). One study found an improvement in psychotic symptoms, but no statistically significant improvement in depressive symptoms with seven days of mifepristone treatment (DeBattista et al., 2006). Another found improvement of Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D), Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGI), and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) scores in patients with psychotic depression after six days of mifepristone (Simpson et al., 2005). A 2009 multisite trial by Blasey et al. found no statistically significant improvement in psychotic symptoms in patients with psychotic depression after seven days of treatment with mifepristone, but they observed that the response rate was significantly increased in patients with mifepristone blood levels greater than or equal to 1800 ng/ml compared to placebo.

For additional information on the biology of depression, see Episode 155: Is Depression a Chemical Imbalance?

Treatment for Psychotic Depression

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2022 guidelines recommend a first-line treatment for psychotic depression involving a combination of antidepressant and antipsychotic medications, specifically highlighting the effectiveness of olanzapine and quetiapine in combination with antidepressants (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2022). Quetiapine was noted for its antidepressant profile as well. Once acute symptoms improve, they advise adding psychotherapy. Electroconvulsive therapy is considered for patients with a strong preference based on positive experiences, a need for rapid response, or when other treatments have been unsuccessful.

Antidepressants + Antipsychotics

Chronic use of typical antidepressants, such as SSRIs, leads to slow increases in neurotrophic factor expression, including BDNF, though they do not increase the release of BDNF (Duman & Aghajanian, 2012). Conventional antidepressants also increase synaptic neuroplasticity, and this response seems to require BDNF (Duman & Aghajanian, 2012).

Generally, escalating SSRI dosing beyond the therapeutic range does not improve efficacy. Conversely, some evidence suggests that higher dosages of tricyclic antidepressants, venlafaxine, and tranylcypromine may convey additional efficacy for patients with treatment-resistant depression (Adli et al., 2005).

Although evidence is limited, the combination of antidepressants (typically SSRIs) with antipsychotics is considered first line treatment for patients with psychotic depression. In a Cochrane systematic review synthesizing findings across five studies, Kruizinga et al. (2021) reported low‐ to very low‐certainty evidence of enhanced depression response rates with dual therapy using antipsychotics combined with antidepressants over monotherapy with antidepressants alone, antipsychotics alone, or placebo alone, in patients with psychotic depression.

Antipsychotic Maintenance Therapy

Current evidence suggests that patients with psychotic depression should continue both antipsychotic and antidepressant medications well after remission.

In the STOP-PD II trial by Flint et al. (2019), 126 patients with psychotic depression treated with dual antidepressant and antipsychotic therapy were randomized to either sertraline + olanzapine or sertraline + placebo maintenance therapy.

After 36 weeks, patients receiving both SSRI + antipsychotic therapy had a relapse rate of 20.3% compared to 54.8% in the SSRI + placebo cohort.

Most notably, patients receiving the placebo experienced higher relapse rates of depression without psychosis (18 vs. 5), depression with psychosis (11 vs. 4), suicide plan or attempt (3 vs. 0), and psychiatric hospitalization (11 vs. 6).

However, “This benefit needs to be balanced against potential adverse effects of olanzapine, including weight gain” (Flint et al., 2019).

ECT

Robust evidence supports the effectiveness of electroconvulsive therapy in treating psychotic depression. A significant clinical trial by Petrides et al. (2001) demonstrated compelling results: a 95% remission rate in patients with psychotic depression, compared to 83% remission in those with non-psychotic depression. This highlights the potential of ECT as a highly effective treatment modality for psychotic depression.

A more recent retrospective analysis of 34 depressed patients without psychotic symptoms and 31 with psychotic symptoms found that both the presence of psychotic symptoms and higher psychotic depression assessment scale (PDAS) scores were predictive of response and remission in electroconvulsive therapy for depression, particularly in older patients (van Diermen et al., 2019).

Ketamine

According to Duman & Aghajanian (2012):

In contrast to medications like SSRIs that typically take weeks to become effective, ketamine is an NMDA receptor antagonist that has demonstrated rapid antidepressant effects (within hours) that last roughly 7 to 10 days. It is also used to treat bipolar depression and suicidal ideation.

Ketamine quickly increases glutamate neurotransmission, in addition to improving synaptic connectivity and plasticity in mood-regulating areas of the brain, providing evidence that synaptic dysfunction is a key component of depression pathophysiology.

Ketamine increases BDNF release, as opposed to SSRIs, which only increase BDNF expression, and ketamine-induced synaptogenesis (creation of new synaptic connections between neurons) requires BDNF.

The use of ketamine in depression treatment faces limitations due to its psychotomimetic effects, which can mimic symptoms of psychosis, as well as its potential for abuse.

Especially given the psychotomimetic effects, people with psychotic depression may not be good candidates for long-term therapeutic use of ketamine.

Comparing ECT, Ketamine, and rTMS

Interventional psychiatry includes electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), and ketamine, all of which have been studied in psychotic depression.

Ketamine vs. ECT

KetECT by Ekstrand et al. (2022)

This study of 186 hospital inpatients with unipolar depression found ketamine to be inferior to ECT, with 63% of patients who received ECT achieving remission and 46% of patients who received ketamine infusions. Both groups required a median of 6 sessions.

While ECT was associated with more serious and lasting adverse effects like persistent amnesia, ketamine led to more patient dropouts due to treatment-emergent adverse effects–23% in the ketamine group dropped out before 6 infusions, while 3% dropped out from the ECT group. This might be partially explained by both patients and staff having less familiarity with what adverse effects they could expect from ketamine treatment compared with the better-known side effects of ECT, as well as patients knowing that they would be able to receive ECT at the end of the study regardless of dropping out of the ketamine treatment group.

In this study, among patients with psychotic depression, 79% who received ECT achieved remission, compared to 50% in the ketamine group. However, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.15). This p-value indicates that, under the assumption of no true difference between the treatments, there is a 15% probability of observing a difference as large as or larger than the one observed due to random chance. The study did not reach the commonly used threshold for statistical significance (p < 0.05), which might be attributable to the small sample size in both treatment arms, potentially reducing the study's power to detect significant differences.

Furthermore, patients receiving ECT showed greater improvements in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) scores, but this difference also did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.069). This p-value suggests a 6.9% probability of observing such a difference or more by chance alone if no true difference exists. This is slightly above the conventional 5% threshold (p < 0.05) typically required to declare statistical significance. The limited number of patients with psychotic depression in the sample (14 in the ECT group and 18 in the ketamine group) may contribute to this lack of statistical significance. However, the observed effect size (Cohen's d = 0.68) for the difference in final MADRS scores is notable, indicating a medium effect size and suggesting that ECT might indeed be more effective than ketamine for patients with psychotic depression, despite the lack of statistical significance.

Another subgroup analysis revealed that patients older than 50 years were more likely to remit with ECT (77% of older patients vs. 50% of those younger than 50) but less likely to achieve remission with ketamine (37% of older patients and 61% of younger patients). This finding is consistent with previous research demonstrating high efficacy of ECT in older patients (Geduldig & Kellner 2016), as well as evidence of ketamine treatment failure in older adults (Szymkowicz et al., 2014).

Among those who initially achieved remission, there was no difference in the proportion of patients whose depression relapsed within 12 months (70% in the ketamine group vs 63% who received ECT, P = 0.52), indicating similar long-term effectiveness between the two treatments. These data underscore the importance of long-term follow-up after remission of depression and the necessity for multimodal treatment approaches.

ELEKT-D by Anand et al. (2023)

This study found ketamine noninferior to ECT in 403 outpatients with treatment-resistant depression, but excluded patients with psychotic depression. Over three weeks, patients were randomized to receive either ECT three times per week or a subanesthetic dose of ketamine (0.5mg per kg) given intravenously over 40 minutes twice per week. The primary outcome was treatment response, defined as ≥50% decrease in Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self-Report (QIDS SR) scores. In the ketamine group, 55.4% of patients responded to treatment, compared to 41.2% of patients in the ECT group, meeting the predefined threshold for concluding the noninferiority of ketamine to ECT in the studied outpatients with nonpsychotic depression.

ECT vs. rTMS

There is evidence to suggest that rTMS helps with auditory hallucinations (Gornerova et al., 2023), and this retrospective, register-based, naturalistic study by Strandberg et al. (2023) used a cross-over design to compare ECT with rTMS in a sample of 138 patients with depression who had received both ECT and rTMS across 19 hospitals in Sweden. They did not exclude patients with psychotic depression, and 44.2% of those in the ECT group were taking antipsychotics, as were 48.6% of those receiving rTMS.

The authors found that ECT was more effective than rTMS for decreasing symptoms of depression, with response rates of 38% for ECT and 15% for rTMS. Response was defined as 50% reduction in the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale—Self-report (MADRS-S) score. MADRS-S score improved on average by 15 points with ECT and 5.6 points with rTMS.

Lithium Augmentation

Although they are no longer considered up-to-date, the 2010 American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines recommended lithium as an augmentation therapy for psychotic depression in patients already receiving treatment with antidepressants and antipsychotics (Gelenberg et al., 2010). Notably, lithium has been shown to enhance suicide prevention, which is a significant concern in patients with psychotic depression (Bassett et al., 2022). However, there are no randomized or large-scale studies evaluating lithium efficacy specifically in psychotic depression. It is also unclear whether antipsychotics combined with mood stabilizers are more effective than mood stabilizer monotherapy in psychotic bipolar depression (Rothschild, 2013).

Although the quality of evidence is weak, Rothschild (2013) cites four uncontrolled retrospective studies that demonstrated improved response rates for psychotic depression, particularly in patients with bipolar disorder, when lithium was added to treatment with a combination of antidepressants and antipsychotics.

Despite little evidence on its use in psychotic depression specifically, lithium augmentation has been studied in patients with nonpsychotic depression who partially respond to antidepressant therapy (Rothschild, 2013). A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis by Vázquez et al. found that augmentation of antidepressant treatment with lithium seems to be more effective, with fewer adverse effects than augmentation with second-generation antipsychotics or esketamine.

Psychotherapy

The article by Gaudiano & Herbert (2006) suggests that acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for psychotic depression (PD) patients can lead to significant improvements, with 44% of the PD patients in the ACT group showing clinically significant improvement by discharge (≥2 SD change in Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale), compared to 0% in the enhanced treatment as usual group.

In the realm of treating more complex forms of depression, it has been thought that the efficacy of psychotherapy as a standalone treatment diminishes with increased depression severity or complexity (Dubovsky et al., 2021). However, the studies generally cited are discussion papers or original research with weak quality of evidence (i.e., small, uncontrolled, retrospective studies).

Cognitive-based therapies have shown promise in enhancing coping mechanisms among patients with mood disorders who experience delusional symptoms (Rückl et al., 2015). We discussed psychotherapy for patients with psychosis in episode 180 with Michael Garrett. Additional psychotherapeutic approaches that are employed as complementary treatments include behavioral activation and acceptance and commitment therapy (Rothschild, 2013). In Dr. Puder’s clinical experience, partial hospitalization (psychotherapy groups 7 hours per day, 5 days per week) should be considered in all patients with depression and psychosis either as an alternative to ECT or even after ECT.

A Proposed Treatment Algorithm From Dr. Cummings and Dr. Puder

See Figure 1 for a summary algorithm for psychotic depression, which includes the following recommendations:

First, exclude alternative diagnoses, including primary psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder/depression with mixed features, delirium, borderline personality disorder, catatonia, or meth-induced psychosis.

For patients with unipolar psychotic depression, consider a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) plus antipsychotic, typically a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA). Also consider partial hospitalization, and lifestyle things like exercise and diet optimization.

Consider partial hospitalization.

For patients with severe illness who are not progressing in an outpatient setting, consider hospitalization with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

References:

Adli, M., Baethge, C., Heinz, A., Langlitz, N., & Bauer, M. (2005). Is dose escalation of antidepressants a rational strategy after a medium-dose treatment has failed? A systematic review. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience, 255(6), 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-005-0579-5

Al Farsi, R. S., Al Alawi, A. M., Al Huraizi, A. R., Al-Saadi, T., Al-Hamadani, N., Al Zeedy, K., & Al-Maqbali, J. S. (2023). Delirium in Medically Hospitalized Patients: Prevalence, Recognition and Risk Factors: A Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of clinical medicine, 12(12), 3897. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12123897

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Depressive Disorders. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787.x04_Depressive_Disorders

Anand, A., Mathew, S. J., Sanacora, G., Murrough, J. W., Goes, F. S., Altinay, M., Aloysi, A. S., Asghar-Ali, A. A., Barnett, B. S., Chang, L. C., Collins, K. A., Costi, S., Iqbal, S., Jha, M. K., Krishnan, K., Malone, D. A., Nikayin, S., Nissen, S. E., Ostroff, R. B., Reti, I. M., … Hu, B. (2023). Ketamine versus ECT for Nonpsychotic Treatment-Resistant Major Depression. The New England journal of medicine, 388(25), 2315–2325. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2302399

Baethge, C., Baldessarini, R. J., Freudenthal, K., Streeruwitz, A., Bauer, M., & Bschor, T. (2005). Hallucinations in bipolar disorder: characteristics and comparison to unipolar depression and schizophrenia. Bipolar disorders, 7(2), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00175.x

Bassett, D., Boyce, P., Lyndon, B., Mulder, R., Parker, G., Porter, R., Singh, A., Bell, E., Hamilton, A., Morris, G., & Malhi, G. S. (2022). Guidelines for the management of psychosis in the context of mood disorders. Schizophrenia research, 241, 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2022.01.047

Belohradova Minarikova, K., Prasko, J., Holubova, M., Vanek, J., Kantor, K., Slepecky, M., Latalova, K., & Ociskova, M. (2022). Hallucinations and Other Psychotic Symptoms in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 18, 787–799. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S360013

Blasey, C. M., Debattista, C., Roe, R., Block, T., & Belanoff, J. K. (2009). A multisite trial of mifepristone for the treatment of psychotic depression: a site-by-treatment interaction. Contemporary clinical trials, 30(4), 284–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2009.03.001

Bschor, T., Bauer, M., & Adli, M. (2014). Chronic and treatment resistant depression: diagnosis and stepwise therapy. Deutsches Ärzteblatt international, 111(45), 766–775. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2014.0766

Buck, B., Norr, A., Katz, A., Gahm, G. A., & Reger, G. M. (2019). Reductions in reported persecutory ideation and psychotic-like experiences during exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry research, 272, 190–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.022

Cavaco, T. B., & Ribeiro, J. S. (2023). Drawing the Line Between Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Schizophrenia. Cureus, 15(3), e36227. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.36227

Carlson G. A. (2013). Affective disorders and psychosis in youth. Child and adolescent psychiatric clinics of North America, 22(4), 569–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2013.04.003

Cavelti, M., Thompson, K., Chanen, A. M., & Kaess, M. (2021). Psychotic symptoms in borderline personality disorder: developmental aspects. Current opinion in psychology, 37, 26–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.07.003

Cheng, L., Zhu, J., Ji, F., Lin, X., Zheng, L., Chen, C., Chen, G., Xie, Z., Xu, Z., Zhou, C., Xu, Y., & Zhuo, C. (2019). Add-on atypical anti-psychotic treatment alleviates auditory verbal hallucinations in patients with chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuroscience letters, 701, 202–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2019.02.043

Clifford, G., Dalgleish, T., & Hitchcock, C. (2018). Prevalence of auditory pseudohallucinations in adult survivors of physical and sexual trauma with chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Behaviour research and therapy, 111, 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.10.015

Compean, E., & Hamner, M. (2019). Posttraumatic stress disorder with secondary psychotic features (PTSD-SP): Diagnostic and treatment challenges. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry, 88, 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.08.001

Coryell, W., Pfohl, B., & Zimmerman, M. (1984). The clinical and neuroendocrine features of psychotic depression. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 172(9), 521–528. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-198409000-00002

Crow T. J. (2007). How and why genetic linkage has not solved the problem of psychosis: review and hypothesis. The American journal of psychiatry, 164(1), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.13

DeBattista, C., Belanoff, J., Glass, S., Khan, A., Horne, R. L., Blasey, C., Carpenter, L. L., & Alva, G. (2006). Mifepristone versus placebo in the treatment of psychosis in patients with psychotic major depression. Biological psychiatry, 60(12), 1343–1349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.034

Domschke K. (2013). Clinical and molecular genetics of psychotic depression. Schizophrenia bulletin, 39(4), 766–775. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbt040

Dubovsky, S. L., Ghosh, B. M., Serotte, J. C., & Cranwell, V. (2021). Psychotic Depression: Diagnosis, Differential Diagnosis, and Treatment. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 90(3), 160–177. https://doi.org/10.1159/000511348

Duman, R. S., & Aghajanian, G. K. (2012). Synaptic dysfunction in depression: potential therapeutic targets. Science (New York, N.Y.), 338(6103), 68–72. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1222939

D'Agostino, A., Rossi Monti, M., & Starcevic, V. (2019). Psychotic symptoms in borderline personality disorder: an update. Current opinion in psychiatry, 32(1), 22–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000462

Ekstrand, J., Fattah, C., Persson, M., Cheng, T., Nordanskog, P., Åkeson, J., Tingström, A., Lindström, M. B., Nordenskjöld, A., & Movahed Rad, P. (2022). Racemic Ketamine as an Alternative to Electroconvulsive Therapy for Unipolar Depression: A Randomized, Open-Label, Non-Inferiority Trial (KetECT). The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology, 25(5), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyab088

Gaudiano, B. A., Dalrymple, K. L., & Zimmerman, M. (2009). Prevalence and clinical characteristics of psychotic versus nonpsychotic major depression in a general psychiatric outpatient clinic. Depression and anxiety, 26(1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20470

Fiorentini, A., Cantù, F., Crisanti, C., Cereda, G., Oldani, L., & Brambilla, P. (2021). Substance-Induced Psychoses: An Updated Literature Review. Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, 694863. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.694863

Flint, A. J., Meyers, B. S., Rothschild, A. J., Whyte, E. M., Alexopoulos, G. S., Rudorfer, M. V., Marino, P., Banerjee, S., Pollari, C. D., Wu, Y., Voineskos, A. N., Mulsant, B. H., & STOP-PD II Study Group (2019). Effect of Continuing Olanzapine vs Placebo on Relapse Among Patients With Psychotic Depression in Remission: The STOP-PD II Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 322(7), 622–631. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.10517

Gaudiano, B. A., & Herbert, J. D. (2006). Acute treatment of inpatients with psychotic symptoms using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Pilot results. Behaviour research and therapy, 44(3), 415-437.

Gaudiano, B. A., & Zimmerman, M. (2010). The relationship between childhood trauma history and the psychotic subtype of major depression. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica, 121(6), 462–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01477.x

Geduldig, E. T., & Kellner, C. H. (2016). Electroconvulsive Therapy in the Elderly: New Findings in Geriatric Depression. Current psychiatry reports, 18(4), 40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0674-5

Gelenberg, A.J., Freeman, M.P., Markowitz, J.C., Rosenbaum, J.F., Thase, M.E., Trivedi, M.H., Van Rhoads, R.S. (2010). PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder (3rd ed.). American Psychiatric Association. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf

Gornerova, N., Brunovsky, M., Klirova, M., Novak, T., Zaytseva, Y., Koprivova, J., Bravermanova, A., & Horacek, J. (2023). The effect of low-frequency rTMS on auditory hallucinations, EEG source localization and functional connectivity in schizophrenia. Neuroscience letters, 794, 136977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2022.136977

Grelotti, D. J., Kanayama, G., & Pope, H. G., Jr (2010). Remission of persistent methamphetamine-induced psychosis after electroconvulsive therapy: presentation of a case and review of the literature. The American journal of psychiatry, 167(1), 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08111695

Hamner, M. B., Frueh, B. C., Ulmer, H. G., & Arana, G. W. (1999). Psychotic features and illness severity in combat veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological psychiatry, 45(7), 846–852. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00301-1

Hinterbuchinger, B., Koch, M., Trimmel, M., Litvan, Z., Baumgartner, J., Meyer, E. L., Friedrich, F., & Mossaheb, N. (2023). Psychotic-like experiences in non-clinical subgroups with and without specific beliefs. BMC psychiatry, 23(1), 397. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04876-9

Howland R. H. (2008). Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D). Part 2: Study outcomes. Journal of psychosocial nursing and mental health services, 46(10), 21–24. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20081001-05

Huang, Y., Sun, P., Wu, Z., Guo, X., Wu, X., Chen, J., Yang, L., Wu, X., & Fang, Y. (2023). Comparison on the clinical features in patients with or without treatment-resistant depression: A National Survey on Symptomatology of Depression report. Psychiatry research, 319, 114972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114972

Inouye, S. K., Westendorp, R. G., & Saczynski, J. S. (2014). Delirium in elderly people. Lancet (London, England), 383(9920), 911–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60688-1

Johnson, J., Horwath, E., & Weissman, M. M. (1991). The validity of major depression with psychotic features based on a community study. Archives of general psychiatry, 48(12), 1075–1081. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360039006

Kruizinga, J., Liemburg, E., Burger, H., Cipriani, A., Geddes, J., Robertson, L., Vogelaar, B., & Nolen, W. A. (2021). Pharmacological treatment for psychotic depression. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 12(12), CD004044. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004044.pub5

Krynicki, C. R., Upthegrove, R., Deakin, J. F. W., & Barnes, T. R. E. (2018). The relationship between negative symptoms and depression in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica, 137(5), 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12873

McIntyre, R. S., Lee, Y., & Mansur, R. B. (2016). A pragmatic approach to the diagnosis and treatment of mixed features in adults with mood disorders. CNS spectrums, 21(S1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1017/S109285291600078X

Mullen, J. M., Richards, J. R., & Crawford, A. T. (2023). Amphetamine-Related Psychiatric Disorders. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2022). Depression in Adults: treatment and management [NG 222]. Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng222

Nordahl, T. E., Salo, R., & Leamon, M. (2003). Neuropsychological effects of chronic methamphetamine use on neurotransmitters and cognition: a review. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 15(3), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.15.3.317

Paljärvi, T., Tiihonen, J., Lähteenvuo, M., Tanskanen, A., Fazel, S., & Taipale, H. (2023). Psychotic depression and deaths due to suicide. Journal of affective disorders, 321, 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.10.035

Peng, P., Wang, Q., Ren, H., Zhou, Y., Hao, Y., Chen, S., Wu, Q., Li, M., Wang, Y., Yang, Q., Wang, X., Liu, Y., Ma, Y., Li, H., Liu, T., & Zhang, X. (2023). Association between thyroid hormones and comorbid psychotic symptoms in patients with first-episode and drug-naïve major depressive disorder. Psychiatry research, 320, 115052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115052

Perlis, R. H., Uher, R., Ostacher, M., Goldberg, J. F., Trivedi, M. H., Rush, A. J., & Fava, M. (2011). Association between bipolar spectrum features and treatment outcomes in outpatients with major depressive disorder. Archives of general psychiatry, 68(4), 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.179

Petrides, G., Fink, M., Husain, M. M., Knapp, R. G., Rush, A. J., Mueller, M., Rummans, T. A., O'Connor, K. M., Rasmussen, K. G., Jr, Bernstein, H. J., Biggs, M., Bailine, S. H., & Kellner, C. H. (2001). ECT remission rates in psychotic versus nonpsychotic depressed patients: a report from CORE. The journal of ECT, 17(4), 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1097/00124509-200112000-00003

Piesse, E., Paulik, G., Mathersul, D., Valentine, L., Kamitsis, I., & Bendall, S. (2023). An exploration of the relationship between voices, dissociation, and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Psychology and psychotherapy, 96(4), 1015–1028. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12493

Rothschild, A. J., Mulsant, B. H., Meyers, B. S., & Flint, A. J. (2006). Challenges in Differentiating and Diagnosing Psychotic Depression. Psychiatric Annals, 36(1), 40-46. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/challenges-differentiating-diagnosing-psychotic/docview/217052563/se-2

Rothschild A. J. (2013). Challenges in the treatment of major depressive disorder with psychotic features. Schizophrenia bulletin, 39(4), 787–796. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbt046

Rückl, S., Gentner, N. C., Büche, L., Backenstrass, M., Barthel, A., Vedder, H., Bürgy, M., & Kronmüller, K. T. (2015). Coping with delusions in schizophrenia and affective disorder with psychotic symptoms: the relationship between coping strategies and dimensions of delusion. Psychopathology, 48(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1159/000363144

Sikich L. (2013). Diagnosis and evaluation of hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms in children and adolescents. Child and adolescent psychiatric clinics of North America, 22(4), 655–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2013.06.005

Simpson, G. M., El Sheshai, A., Loza, N., Kingsbury, S. J., Fayek, M., Rady, A., & Fawzy, W. (2005). An 8-week open-label trial of a 6-day course of mifepristone for the treatment of psychotic depression. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 66(5), 598–602. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v66n0509

Slotema, C. W., Blom, J. D., Niemantsverdriet, M. B. A., Deen, M., & Sommer, I. E. C. (2018). Comorbid Diagnosis of Psychotic Disorders in Borderline Personality Disorder: Prevalence and Influence on Outcome. Frontiers in psychiatry, 9, 84. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00084

Stahl, S. M., Morrissette, D. A., Faedda, G., Fava, M., Goldberg, J. F., Keck, P. E., Lee, Y., Malhi, G., Marangoni, C., McElroy, S. L., Ostacher, M., Rosenblat, J. D., Solé, E., Suppes, T., Takeshima, M., Thase, M. E., Vieta, E., Young, A., Zimmerman, M., & McIntyre, R. S. (2017). Guidelines for the recognition and management of mixed depression. CNS spectrums, 22(2), 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852917000165

Strandberg, P., Nordenskjöld, A., Bodén, R., Ekman, C. J., Lundberg, J., & Popiolek, K. (2023). Electroconvulsive Therapy Versus Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Patients With a Depressive Episode: A Register-Based Study. The journal of ECT, 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000971. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCT.0000000000000971

Szymkowicz, S. M., Finnegan, N., & Dale, R. M. (2014). Failed response to repeat intravenous ketamine infusions in geriatric patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology, 34(2), 285–286. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000000090

Tschöke, S., & Kratzer, L. (2023). Psychotic experiences in trauma-related disorders and borderline personality disorder. The lancet. Psychiatry, 10(1), 5–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00399-6

Ujike, H., & Sato, M. (2004). Clinical features of sensitization to methamphetamine observed in patients with methamphetamine dependence and psychosis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1025, 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1316.035

Ulloa, R. E., Birmaher, B., Axelson, D., Williamson, D. E., Brent, D. A., Ryan, N. D., Bridge, J., & Baugher, M. (2000). Psychosis in a pediatric mood and anxiety disorders clinic: phenomenology and correlates. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(3), 337–345. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200003000-00016

van Diermen, L., Versyck, P., van den Ameele, S., Madani, Y., Vermeulen, T., Fransen, E., Sabbe, B. G. C., van der Mast, R. C., Birkenhäger, T. K., & Schrijvers, D. (2019). Performance of the Psychotic Depression Assessment Scale as a Predictor of ECT Outcome. The journal of ECT, 35(4), 238–244. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCT.0000000000000610

van Os, J., & Reininghaus, U. (2016). Psychosis as a transdiagnostic and extended phenotype in the general population. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 15(2), 118–124. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20310

Vázquez, G. H., Bahji, A., Undurraga, J., Tondo, L., & Baldessarini, R. J. (2021). Efficacy and Tolerability of Combination Treatments for Major Depression: Antidepressants plus Second-Generation Antipsychotics vs. Esketamine vs. Lithium. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 35(8), 890–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/02698811211013579

Yung, A. R., & Lin, A. (2016). Psychotic experiences and their significance. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 15(2), 130–131. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20328

Zimmerman, M., & Mattia, J. I. (1999). Psychotic subtyping of major depressive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 60(5), 311–314. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v60n0508