Episode 157: Polypharmacy in Psychiatry

By listening to this episode, you can earn 1.25 Psychiatry CME Credits.

Other Places to listen: iTunes, Spotify

Article Authors: Jake McBride DO, David Puder, MD

Jake McBride and David Puder have no conflicts of interest to report.

Jacob McBride is a psychiatrist in Pittsburgh, PA. He serves his community through an IOP program and hospital consultations at Saint Clair Health, which is not affiliated with this project. He maintains a private practice, as well, and would be delighted to connect at the contact information below.

Connect with Jake McBride:

412 365 5155

JM@selforganizingsystems.com

Why Look Into Polypharmacy?

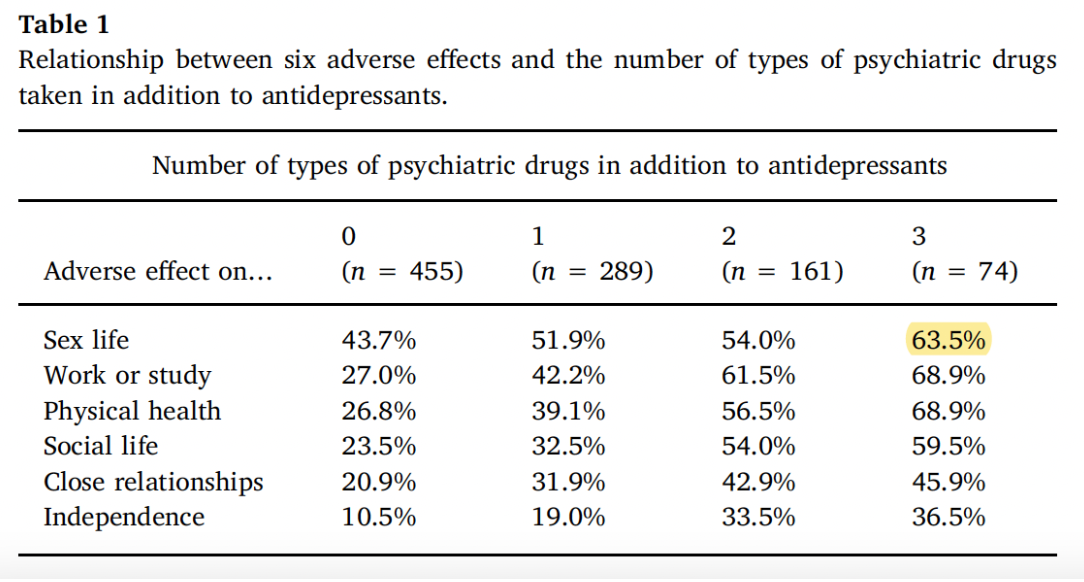

Almost universally, the rate of antidepressant use has risen over the latter half of the century. Read et al. in their 2017 paper note prescriptions for antidepressants in England doubled from 2005 to 2015 and looked at interpersonal interpersonal adverse effects. With a survey of nearly 1800 individuals, they asked about deleterious effects on sex life, vocation, general physical health, social life, close relationships, and independence. One thousand respondents were taking antidepressants at the time of the survey, 484 of which were taking only antidepressants at the time of the survey. Of this latter category, 86% reported at least one of these side effects. Over half of respondents (63.9%) reported mild adverse effects, a third reported moderate adverse effects (32%), and 4.1 % reported severe adverse effects. Sex life distruption was the most common adverse effects at 43.7%, with other categories reported by ¼ to ⅓ of respondents.

Polypharmacy, defined here as an antidepressant with at least one other tranquiliser, antipsychotic, or mood stabilizer, was reported by 524 respondents. In the same way that an endocrinologist will see more complex diabetic patients than a general practitioner, and they will likely be on more medications, a psychiatrist will see more complex patients and therefore tend to have patients with more medications. Of the respondents in this study, 42.6% with polypharmacy were under the care of a psychiatrist, and 12.6% were under the care of a general practitioner. Polypharmacy increased, and in some cases doubled, the risk of the above adverse effects. The total number of psychotropics was correlated with progressive risk of adverse effects, and was inversely correlated to perceived efficacy of the drugs.

Read’s definition of polypharmacy, several drugs in multiple classes, is a common one. There are other ways to define the issue. Polypharmacy can refer to redundancy with multiple drugs in the same class (Kukreja 2013). Adjuvant polypharmacy refers to the use of one drug to treat the adverse effects of another. Polypharmacy through augmentation occurs when one drug’s dose is maximized, but symptoms remain. In these cases, another agent is added to continue to pursue a treatment effect. Additionally there is total polypharmacy, the absolute number of medications regardless of class, mechanism, and indication.

Epidemiology

Polypharmacy is fairly prevalent, though depending on how it is defined and measured, rates vary from 13 to 90% (Kukreja 2013). Up to ⅓ of outpatients are on three or more psychotropics. In 1974, 5% of inpatients were discharged on three or more medications, up to 40% by 1990. In general, multi-class polypharmacy is most prevalent and found in 20.9% of patients (De las Cuevas and Sanz in 2004). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors given with a benzodiazepine are most common, followed by tricyclic antidepressants given with a benzodiazepine. In same-class polypharmacy, multiple benzodiazepines are most common. 19% of child and adolescent patients are reported on multiple classes of psychotropics (Comer 2016).

Why Does Polypharmacy Happen?

Many authors give a variety of reasons polypharmacy occurs, many of which are summarized in Kukreja’s 2013 review article. There are scientific reasons for it (with a focus on biogenic amines), their pharmacodynamics, and their metabolism, and there is an impetus to use medications to address psychiatric conditions (Kukreja 2013). There are also economic reasons for it. The pharmaceutical sector of the US economy is immense, valued at 2.8 trillion dollars (statista.com). Discussion on the ways the pharmaceutical industry influences prescribing exceeds the scope of this essay, but there is an enormous amount of capital that depends on prescribing medications. There are regulatory issues as well - the Food and Drug Administration gives indications for a medication only when safety and efficacy for that indication is demonstrated by the manufacturers. This often leaves professional organizations and individual prescribers to their own interpretation of the literature if they wish to use one medication to treat multiple problems. This is made all the more perilous by the economic problem, as off-label prescribing can be illegally encouraged by drug companies. There’s a cultural issue as well, as Americans may have “a large appetite for pharmacological treatments,” which may or may not be appropriate (Kukreja 2013). Sometimes the problem can lie with the prescriber, either due to compromise from the above factors, or compromise from intrinsic factors.

These intrinsic factors are, at times, mistakes. There can be a lack of conviction about declaring a medication trial to be failed, or less charitably a “combination of fear and laziness,” such that treatment failure is addressed not with discontinuation of a medication, but addition of still more (Kingsbury 2001). When there is diagnostic ambiguity, “sloppy diagnosis,” can lead to treating many potential conditions or symptom clusters, rather than working towards a more parsimonious diagnosis with a more parsimonious treatment plan. If there is a cross titration, and the patient does well, many are tempted to halt the titration and proceed with polypharmacy rather than stick to plan and arrive at one, not two, medications. Inadequate pharmacologic knowledge can lead illogical treatment decisions, such as adding a medication with a similar mechanism of action to a similar one already in use, or using multiple meds at sub therapeutic doses.

Merits

There are times when polypharmacy may be helpful or even necessary. There may be a need due to failure of monotherapy (Sadock 2009). Illness with various phases, such as bipolar d/o, may require many med changes over time, which may necessitate polypharmacy. Comorbidities may require treatment with different agents. When side effects are dose dependent, using more agents at lower doses may avoid these side effects. Adjuvants may be required to respond to adverse effects and other complications. Augmentation can be preferred over switching the initial medication if there is partial response. Symptoms of special concern, like suicidality, may be targeted by the addition of lithium or clozaril. Similar considerations can be seen in other fields, where there is precedent in treating conditions like CHF, epilepsy, cancer, AIDS, etc., which often require polypharmacy.

Demerits

Many concerns arise under a drug regimen with polypharmacy. Adherence becomes more difficult for patients. Cumulative toxicity rises linearly and, where there are interactions, potentially exponentially. Valproate and carbamazepine are a famous example, whereby carbamazepine levels are increased with co-administration, with valproate interfering with its metabolism and also metabolite glucuronidation and clearance (Bernus et al., 1997). It is associated with excessive dosing and early death (Ito et al., 2005). Ito studied 139 patients with schizophrenia across 19 psychiatric units. Polypharmacy and excessive dosing were found in 96 cases. Factors were psychiatrist skepticism towards algorithms, nursing requests, and patient’s clinical condition.

Dealing with Polypharmacy

Minimizing polypharmacy requires a complex knowledge of the patient, their conditions, and the medications. The SAIL (simple, adverse, indication, list) acronym offers a good start at this (Lee 1998). Prescribers are to keep drug regimens simple, with once daily regimens where possible. Adverse effects are to be understood not just for each drug independently, but also within their interactions as well. Drug indications must be clearly understood with a well defined therapeutic goal, and the drug’s progress in meeting that goal must be continually reassessed. Keeping an accurate list, while obvious on the face of it, remains a critical task if any of the above advice is to be followed at all. While general principles are helpful in managing polypharmacy, managing the complexity of polypharmacy often requires more detailed attention to specific issues.

Special Topics In Polypharmacy

Anticholinergic Effects

Joshi et al., 2021 assessed for impacts of other variables with regression analysis for proxies of disease severity, such as total antipsychotic dosage, negative symptom severity, positive symptom severity, number of hospitalizations, and cigarettes per day. They found decrement across all measured cognitive domains, largely independent of the confounding factors above, and correlated in a dose-dependent manner with the anticholinergic burden.

The average ACB score is 3.8, and the anticholinergic burden is high in the studied schizophrenia/schizoaffective population. An ACB over 3 is associated with 50% increased risk of developing dementia. Anticholinergic effects were detected “across all cognitive domains with comparable magnitude.” This did not vary with the type of medication, but varied with ACB, suggesting the concept of total anticholinergic burden is more important than individual medications.

The results suggest “differences in cognitive outcomes associated with antipsychotic medications, if present, likely occur in the context of overall anticholinergic medication burden and may not necessarily reflect other complex difference in dopaminergic / serotonergic blockade,” a likely reference to the 5HT 1A / 2A effects of atypicals and the theoretical cognitive benefit they may provide.

There is one reason to intentionally incur some anticholinergic burden in the treatment of schizophrenia, the prevention or treatment of EPS (if they have a history of EPS or are high risk).

One criticism of the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden scale from agingbraincare.org is that it scores medications even if they have no anticholinergic activity. It assigns a score of 1 for possible anticholinergics, including Abilify, Invega, Risperidone. “Aripiprazole, risperidone, and ziprasidone did not demonstrate AA at any of the concentrations studied,” and “in vitro binding of aripiprazole, risperidone, and ziprasidone is negligible” (Chew 2006) at concentrations up to 1000 ng/dL

Bipolar Disorder

Fornaro et al. in 2016 produced a meta analysis of articles relating to polypharmacy in bipolar disorder. Thirty-one articles met their inclusion criteria. They take pains to discuss one of the main challenges in polypharmacy, which is to define it. While one could describe it as a duplication of med class or mechanism of action for a specific diagnosis, they offer more simple terms: Polypharmacy for the use of 2 or 3 psychotropic medications, and complex polypharmacy for the use of 4 or more psychotropic medications. Prevalence depends on the definition, but as an example, in STEP BD inpatients were on an average of 3.21 +/- 1.46 psychotropics, and 5.94 +/- 3.78 total medications. The Arzneimittelüberwachung in der Psychiatrie Program followed over 2000 cases for 16 years and reported 85% of cases received psychotropic polypharmacy. Of these cases, 15% received monotherapy.

Clinical features of polypharmacy cases are identified. Treatment with second-generation antipsychotics (SGA) drugs, history of suicide attempts, income above $75,000 were associated with higher rates of polypharmacy on analysis of the STEP BD data. Treatment with lithium, valproic acid, and carbamazepine was associated with the lowest rates of polypharmacy. Factors not found to contribute to the risk of polypharmacy include history of psychosis, age of onset, prior hospitalizations, and history of substance use. Neither the subtype (type I vs. II) of bipolar disorder nor the phase of illness (manic, depressed, mixed) contributed to risk. Patients presenting with depression or a mixed episode experienced increased polypharmacy involving selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (45% for depression, 20% for mixed episode) and also benzodiazepines (47% for depression, 33% for mixed episode) (Weinstock 2014). Use of lithium, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics did not vary with episode polarity.

A retrospective chart review of 89 patients, found associations with personality traits as assessed by the revised NEO Five Factor Personality Inventory (Barnett 2010). The low openness group had more current medications (3.7 +/- 1) than those scoring high on openness (2.8 +/- 1.8). Those found using 18 or more medications over their lifespan were found to score low on extraversion and conscientiousness.

Polypharmacy often occurs in the treatment of bipolar disorder while deviating from guidelines. The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety CANMAT guidelines of 2009, with a 66% concordance in the initial approach to mania. Nonconcordant treatment strategies cites include SGA polypharmacy in 22.1%, use of more than one mood stabilizer in 9.6 %, use of carbamazepine in 1/9%, or typical antipsychotics in 0.4%. Guideline adherence fell to 48.7% at the next treatment step. 26.5% of cases adhered to initial treatment of depression guidelines. Overall CANMAT adherence through all phases was 18.6%. For APA guidelines, it is 7.3 % for mania and 5.6% for depression. Broadly speaking, much of the deviation is polypharmacy where not recommended by guidelines.

Polypharmacy in bipolar disorder is common. Treatment plans often do not follow treatment guidelines. The evidence base for antipsychotics and mood stabilizers is an active area of research with room for difference of opinion, and there is plenty of room for reasonable disagreement about the timing and choice of such agents. Unfortunately, a substantial proportion of the deviation from treatment guidelines involves the use of serotonergic agents, which have been shown to be of little use, or even harmful, in the treatment of bipolar disorder. While there is much research to be done in the multi-phasic, complex phenomenon of bipolar disorder, there is also much to be improved in our utilization of the evidence base as it stands today.

Seroquel

It makes sense to consider seroquel for sleep. It has antihistamine, alpha 1-blocking, alpha 2-promoting, anticholinergic, serotonin-modulating, and dopamine-blocking properties. Low doses of seroquel can have some robust effects, with 100% H1 occupancy and 50% D2 occupancy at 50 mg of the drug (Stahl 2013). Aside from interacting with GABA receptors, one would be hard pressed to find a more thorough profile for a sleep aid. A small study by Cohrs in 2004 involving 14 men showed some benefit for seroquel. It was tested by self-report and polysomnography for 3 nights in a row, 3 times, with 4 days in between. Doses of placebo, 25 mg, and 100 mg were given. Seroquel improved subjective reports and there was a dose-dependent increase in stage 2 sleep.

Unfortunately, there’s not much more evidence than that to back its use. For want of data and onerous side effects, neither European (Riemann 2017) nor American authorities recommend its use (Sateia 2017). The UK (BMJ Best Practice) doesn’t mention seroquel at all in their sleep recommendations. It has been studied in conditions where it has a primary indication like bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, with some benefit shown for sleep (Wine 2009). For PTSD, one study showed comparable efficacy for nightmares but with higher dropout due to side effects (Byers 2010).

Antipsychotic Polypharmacy

One major question in psychiatry is the use of more than one antipsychotic to treat psychosis. A 2004 study by Sernyak found psychiatrists report using more than one antipsychotic to reduce positive symptoms in 61% of cases involving polypharmacy, to reduce negative

symptoms in 20%, to decrease the total amount of medication in 9%, and reduction of EPS in 5% (Sernyak 2004). Historically, there’s been little evidence to support use of more than one antipsychotic, however. Most, if not all, treatment guidelines and reviews do not support antipsychotic polypharmacy, with the possible exception of augmenting clozapine (Tiihonen 2021). Yet 10-20% of outpatients with schizophrenia and 40% of inpatients are estimated to be under treatment with more than one antipsychotic.

About ⅓ of patients with schizophrenia respond well to treatment, ⅓ have some response, and ⅓ do not respond. Interest in antipsychotic combinations, therefore, remains. In a 2019 JAMA article, Tiihonen examined data in national registries to study readmission rates in 62,000 patients, and described these rates as a function of various 2 antipsychotic combinations (Tiihonen 2019). Clozaril and Abilify consistently outperformed other combinations as well as monotherapies. Other clozapine combinations and clozapine monotherapy performed better than other combinations and monotherapies, as well. Monotherapy remains the recommendation from most professional organizations, but there is data to provide guidance for clinicians who choose to pursue polypharmacy. However, this data did not have blood level data, which in prior episodes has been discussed as optimally used to bring a singular medication up to the limit of its therapeutic potential prior to switching or adding a second agent.

Conclusion

Becoming an expert at reducing polypharmacy requires being an expert in not only psychopharmacology, but being a coach that directs a patient toward a holistic path. It will likely not be enough to ever just use medications, especially when other themes emerge that need addressing. For example, as a patient has some success with treatment, next they may need to address their sleep apnea, lack of exercise, personality issues that lead to interpersonal conflicts and lack of close relationships. To get them off benzos (over months not weeks) it may require them simultaneously doing psychotherapy more intensely. Walking may not be a big enough dose of exercise to get them producing optimal levels of good hormones that only get increased from strenuous progressive strength training. The patient might need to look deeper at what brings them meaning in logotherapy. Getting off opioids may increase a desire for interpersonal connection which their traumas may cause them to struggle with. The complexity of issues may only grow as you get to know them deeper, but this may also help you know how to better see their issues as more than just something a medication will solve.

Connect with Jake McBride:

412 365 5155

JM@selforganizingsystems.com

References

Barnett JH, Huang J, Perlis RH, Young MM, Rosenbaum JF, Nierenberg AA, Sachs G, Nimgaonkar VL, Miklowitz DJ, Smoller JW. Personality and bipolar disorder: dissecting state and trait associations between mood and personality. Psychol Med. 2011 Aug;41(8):1593-604. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002333. Epub 2010 Dec 7. PMID: 21134316.

Bernus I, Dickinson RG, Hooper WD, Eadie MJ. The mechanism of the carbamazepine-valproate interaction in humans. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997 Jul;44(1):21-7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.00607.x. PMID: 9241092; PMCID: PMC2042805.

Byers MG, Allison KM, Wendel CS, Lee JK. Prazosin versus quetiapine for nighttime posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in veterans: an assessment of long-term comparative effectiveness and safety. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010 Jun;30(3):225-9. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181dac52f. PMID: 20473055.

Chew ML, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Lehman ME, Greenspan A, Kirshner MA, Bies RR, Kapur S, Gharabawi G. A model of anticholinergic activity of atypical antipsychotic medications. Schizophr Res. 2006 Dec;88(1-3):63-72. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.07.011. Epub 2006 Aug 22. PMID: 16928430.

Cohrs S, Rodenbeck A, Guan Z, Pohlmann K, Jordan W, Meier A, Rüther E. Sleep-promoting properties of quetiapine in healthy subjects. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004 Jul;174(3):421-9. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1759-5. Epub 2004 Mar 17. PMID: 15029469. (not free)

Debernard KAB, Frost J, Roland PH. Quetiapine is not a sleeping pill. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2019 Sep 16;139(13). English, Norwegian. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.19.0205. PMID: 31556541.

Fornaro M, De Berardis D, Koshy AS, Perna G, Valchera A, Vancampfort D, Stubbs B. Prevalence and clinical features associated with bipolar disorder polypharmacy: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016 Mar 31;12:719-35. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S100846. PMID: 27099503; PMCID: PMC4820218.

Ito H, Koyama A, Higuchi T. Polypharmacy and excessive dosing: psychiatrists' perceptions of antipsychotic drug prescription. Br J Psychiatry. 2005 Sep;187:243-7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.3.243. PMID: 16135861.

Joshi YB, Thomas ML, Braff DL, Green MF, Gur RC, Gur RE, Nuechterlein KH, Stone WS, Greenwood TA, Lazzeroni LC, MacDonald LR, Molina JL, Nungaray JA, Radant AD, Silverman JM, Sprock J, Sugar CA, Tsuang DW, Tsuang MT, Turetsky BI, Swerdlow NR, Light GA. Anticholinergic Medication Burden-Associated Cognitive Impairment in Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2021 Sep 1;178(9):838-847. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20081212. Epub 2021 May 14. PMID: 33985348; PMCID: PMC8440496.

Kingsbury, S., MG., Ph.D., Donna Yi, M.D., and George M. Simpson, M.D. Psychopharmacology: Rational and Irrational Polypharmacy. Psychiatric Services, online 1 Aug 2001.

Kukreja S, Kalra G, Shah N, Shrivastava A. Polypharmacy in psychiatry: a review. Mens Sana Monogr. 2013 Jan;11(1):82-99. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.104497. PMID: 23678240; PMCID: PMC3653237.

Lee-Chiong T, Malik V. Insomnia. BMJ Best Practice. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/227 Read 19.4.2018. (Not free)

Lee D. Polypharmacy: A Case Report and New Protocol for Management. The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice Mar 1998, 11 (2) 140-144; DOI: 10.3122/15572625-11-2-140

Modesto-Lowe V, Harabasz AK, Walker SA. Quetiapine for primary insomnia: Consider the risks. Cleve Clin J Med. 2021 May 3;88(5):286-294. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.88a.20031. PMID: 33941603.

Read J, Gee A, Diggle J, Butler H. The interpersonal adverse effects reported by 1008 users of antidepressants; and the incremental impact of polypharmacy. Psychiatry Res. 2017 Oct;256:423-427. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.07.003. Epub 2017 Jul 3. PMID: 28697488.

Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C, Bjorvatn B, Dolenc Groselj L, Ellis JG, Espie CA, Garcia-Borreguero D, Gjerstad M, Gonçalves M, Hertenstein E, Jansson-Fröjmark M, Jennum PJ, Leger D, Nissen C, Parrino L, Paunio T, Pevernagie D, Verbraecken J, Weeß HG, Wichniak A, Zavalko I, Arnardottir ES, Deleanu OC, Strazisar B, Zoetmulder M, Spiegelhalder K. European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res. 2017 Dec;26(6):675-700. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12594. Epub 2017 Sep 5. PMID: 28875581.

Sadock, B. J., & Sadock, V. A. (Eds.). (2009). (9th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publishers

Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, Neubauer DN, Heald JL. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017 Feb 15;13(2):307-349. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6470. PMID: 27998379; PMCID: PMC5263087.

Stahl SM. Stahls Essential Psychopharmacology. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Weinstock LM, Gaudiano BA, Epstein-Lubow G, Tezanos K, Celis-Dehoyos CE, Miller IW. Medication burden in bipolar disorder: a chart review of patients at psychiatric hospital admission. Psychiatry Res. 2014 Apr 30;216(1):24-30. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.01.038. Epub 2014 Feb 1. PMID: 24534121; PMCID: PMC3968952.

Wine JN, Sanda C, Caballero J. Effects of Quetiapine on Sleep in Nonpsychiatric and Psychiatric Conditions. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2009;43(4):707-713. doi:10.1345/aph.1L320 (not free)