Episode 147: PANS & PANDAS

By listening to this episode, you can earn 1.5 Psychiatry CME Credits.

Other Places to listen: iTunes, Spotify

Article Authors: Annabel Kuhn, MD, Sarah O’Dor, PhD, Kyle Williams, MD PhD, David Puder MD

Kyle Williams, MD, PHD conflicts of interest:

Octapharma Pharmazeutika Produktionsges.m.b.H.: Research Support

PANDAS Network: Research Support

PANDAS Physicians Network: Research Support

International Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Foundation: Research Support

F-Prime Bioscience Research Initiative: Research Support

Sarah O'Dor, PhD

Octapharma Pharmazeutika Produktionsges.m.b.H.: Research Support

International Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Foundation: Research Support

David Puder and Annabel Kuhn

No conflicts of interest

Kyle Williams, MD, PhD is the founder and director of the Pediatric Neuropsychiatry and Immunology Program at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Williams is a practicing child psychiatrist and neuroscientist, and his research involves the intersection of infections, inflammation and psychiatrist disorders in adults and children. Dr. Williams completed his adult and child psychiatry training at the Yale Child Study Center and completed a PhD in Investigative Medicine (with a concentration on neuroimmunology) at the Yale Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. His primary research and clinical focus is on post-infectious and inflammation-related causes of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and movement disorders.

Dr. Williams’ fascination in neuroscience and OCD began when he was an undergraduate student. He was inspired by this study that explored FDG-PET as a tool to predict response to behavioral therapy versus pharmacotherapy. He worked as a tennis coach for a child living with tourette’s syndrome. Dr. Williams spoke with this child's family, who thought that the child’s symptoms were potentially due to a strep infection. They noticed that his tourette's symptoms worsened each time he had a strep infection. Dr. Williams began researching strep and OCD, and came across a paper by Sue Swedo and Judy Rapoport, the individuals credited for discovering the concept of PANDAS/PANS.

After college, Dr. Williams worked at the NIMH (National Institute of Mental Health) where he explored OCD and related disorders before he began medical school in Minnesota. In medical school, he worked with a researcher who explored OCD in a family who lived in Salt Lake City Utah. Dr. Williams went to Salt Lake City to work with this family, in which there were five generations of strep infections. The oldest generation of that family had high rates of Sydenham Chorea which is a movement disorder that results after a strep infection. Individuals with Sydenham chorea had high rates of new onset obsessive compulsive symptoms. Sydenham chorea is a model for PANDAS. PANDAS is characterized as an infection that developed into OCD but without characteristic movements related to Sydenham chorea. Dr. Williams left Salt Lake City thinking that what they saw was a genetic mutation resulting in a type of OCD similar to pandas which was specific to this particular family. But as it turned out, there is an outbreak of rheumatic fever and Syndenham chorea every 10-15 years in the Salt Lake City area. Furthermore, there is a clone of group A strep (GAS) specific to that region. Dr. Williams took two years off from medical school to study that GAS clone in an infectious disease lab to see if anything about that clone could cause PANS/PANDAS. He then finished medical school, adult psychiatry residency, child and adolescent psychiatry fellowship, all while maintaining his focus on PANS/PANDAS.

Sarah O'Dor, PhD, is the Director of Research of the Pediatric Neuropsychiatry and Immunology Program at Massachusetts General Hospital and Instructor at Harvard Medical School. Her research utilizes neuroimaging, randomized control trials, and neurocognitive assessments to better understand and treat neuropsychiatric disorders in children, particularly OCD, anxiety, and PANDAS. She is also a practicing clinical child psychologist specializing in neuropsychological assessments for children, adolescents, and young adults.

Dr. O’Dor has a background in clinical child psychology. While an intern at MGH, she provided CBT for one of Dr. William’s patients who was living with PANDAS. Dr. O’Dor was intrigued by the fluctuations in the patient’s OCD symptoms, as they were often chronologically linked to when the patient had an infection. Excited by the possibility that PANDAS provided a model for understanding the mechanisms of why some children developed neuropsychiatric symptoms, she changed the focus of her research to PANDAS.

What is PANDAS/PANS?

PANS/PANDAS is the hypothesis that there are certain types of obsessive compulsive symptoms, tic symptoms or restrictive eating symptoms that are caused by an infection and the immune response to an infection. At this point, by clinical criteria, PANDAS and PANS can only be diagnosed in children, and much of the focus on these diagnoses have been on children. Dr. Williams says that it may be possible that this diagnosis might extend to adults. Dr. Williams and Dr. O’Dor have heard of isolated reports of young adults (around ages 18-20) reporting symptoms that resemble PANDAS/PANS, but are not aware of individuals over the age of thirty years developing new onset obsessive compulsive symptoms, movement symptoms, or restrictive eating symptoms related to recent infection.

PANDAS stands for Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Group A Streptococci. It describes a subset of children whose symptoms of OCD or tic disorders are exacerbated by a group A strep infection. After a strep infection clears, a child develops new onset, rapid obsessive compulsive or movement disorder symptoms. PANDAS is specifically tied to a strep infection such as strep throat.

PANS stands for Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome. It describes a clinical syndrome in which OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder) or tics are associated with a non-infectious or infectious trigger. PANS is similar to PANDAS in that it involves rapid onset obsessive compulsive symptoms or tic symptoms but it can be due to any infection such as COVID-19, pneumonia, and more. PANS can also involve new onset avoidant or restrictive eating symptoms following an infectious trigger.

The mechanisms for PANDAS is still a hypothesis. What do we know so far about why these symptoms develop after a strep infection?

Briefly:

Studies that immunized mice with Group A Streptococcal bacteria found the mice displayed abnormal behaviors and deposition of antibodies in various brain structures after immunization. (Yaddanapudi 2010)

Additional mouse studies have shown it is possible for immune cells (T-cells) to cross the blood brain barrier following repeated infection with Group A Streptococcus (Dileepan et al., 2015).

Antibodies from children with PANDAS were found to preferentially bind to a specific type of neuron (in both human and mouse brain) called a Cholinergic Interneuron (CIN) (Xu et al., 2021). These cells are part of a network of neurons in a pathway called the Cortico-Striatal-Thalamo-Cortical (CSTC) circuit, which has been implicated in OCD symptoms. These antibodies were specifically directed against these neurons (and not other types) and were present in higher concentrations in PANDAS patients compared to age-matched healthy children. These antibodies also decreased in concentration after treatment, and as OCD symptoms improved. (Xu et al., 2021)

Two population-based studies utilizing the Danish health registry reported significantly increased risk of developing OCD following either a Group A Streptococcal infection or other bacterial infections (Orlovska, S. et al., 2017, Köhler-Forsberg, O. et al., 2019).

What Is The History Of PANS/PANDAS?

Researchers at the National Institute of Mental Health studying OCD were investigating a previously recognized link between OCD and Sydenham Chorea in children (SC). SC is a movement disorder characterized by rhythmic, involuntary muscle movements (chorea), hypotonia, and neuropsychiatric symptoms; a substantial degree of patients also display new-onset OCD symptoms. It is a major clinical manifestation of Acute Rheumatic Fever, an inflammatory disease which develops in the weeks to months following a streptococcal infection in a small percentage of individuals. In an attempt to recruit children with SC, these investigators found a subset of children with a “strep” infection preceding a sudden and severe onset of OCD, but these children did not meet criteria for SC because they lacked chorea. This subset of children provided the diagnostic framework which would become PANDAS and, later, PANS.

What Causes Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)?

Obsessive compulsive disorder is a disorder in which a person has intrusive, recurring thoughts (obsessions) and/or behaviors (compulsions) that he or she feels the urge to repeat over and over. According to this epidemiological study, OCD affects 2% of the general population. According to the NIMH, the causes of OCD are unknown. Dr. Williams states that no single gene has been identified as causing OCD, and it is most likely that many genes are involved. Heritability seems to play a role and according to the NIMH, “twin and family studies have shown that people with first-degree relatives (such as a parent, sibling, or child) who have OCD are at a higher risk for developing OCD themselves. The risk is higher if the first-degree relative developed OCD as a child or teen”.

There are likely many factors that contribute to the development of OCD. It is possible that an infection could trigger OCD in an individual who is genetically predisposed. PANDAS is one hypothesis as to the cause of OCD. The OCD symptoms in PANDAS are identical to the symptoms of non-PANDAS OCD. Some examples include compulsive hand washing, checking, hoarding behaviors, and many more.

How Can A Parent Recognize OCD Symptoms In A Young Child?

Diagnosing PANDAS is difficult because differentiating OCD or tics related to an infection, versus other reasons, is difficult. Whether or not OCD symptoms are caused by PANDAS, it is important for parents to recognize potential OCD symptoms in their children. Let’s review some common signs of OCD in general in a child at the age of six.

Some examples of signs of new-onset OCD might include significant changes in, and adherence to, routines. A bedtime routine may suddenly consume hours of time. Another sign might be a child suddenly refusing to go to school for no clear reason–the child might fear a situation related to his or her OCD such as germs, or being around certain people. At first, these symptoms may seem developmentally appropriate in children or the expression of a preference, but these behaviors occur at a frequency and intensity so severe that it significantly interferes with daily life and family routines.

Children with OCD may have intrusive thoughts about harming themselves or others, though they may not desire to do so. These obsessions are sometimes followed by the child repeatedly seeking a parent to seek reassurance or confess troubling thoughts; many parents may not realize this reassurance seeking is a compulsive behavior. They may come home and immediately tell their parents about distressing thoughts they had all day while at school.

Handwashing until one’s skin is raw or showering for hours can be seen in children with OCD. Hoarding behaviors can also be recognized in children as young as 5 or 6. A child with OCD might say “I feel badly for this hamburger wrapper so I need to keep it” because he or she is irrationally holding a meaning or emotion about an object which prevents the object from being thrown away. OCD can be thought of poorly assessing risk about something, and subsequently over-attributing individual control over a situation. For example, a child might think “I’m worried about something bad happening to mom and dad so I have to tap the table fifteen times to stop something bad from happening”. The child might feel less anxious initially, until the obsessive thought returns, sometimes minutes later, and they have to respond by performing the compulsion again..

Other OCD symptoms in children include:

Fear of vomiting

Repeating routine activities like opening or closing a door

Avoiding certain family members or other persons out of fear of contracting an illness or some undesirable trait

These are quite complicated symptoms that can exist even at an early age. At such an early age, a child may not be able to clearly describe specificities regarding the anxiety or the need for the compulsion, and may throw tantrums if their symptoms/obsessions are not accommodated.

Mechanism Of PANDAS

We do not know exactly why people develop OCD, the proposed mechanism in PANDAS is that it results from a streptococcus infection and abnormal immune response. One scenario by which this could happen is termed “molecular mimicry”, which suggests that similarities between bacterial and self-proteins are sufficient to result in cross-reactivity of antibodies or T/B cells. In the case of PANDAS, a protein on the surface of the streptococcal bacteria may generate antibodies or cells which react with brain proteins, resulting in PANDAS symptoms. Another hypothesis is that streptococcal infections are uniquely dysregulating to the human immune system in ways other infections are not. Many autoimmune processes are thought to be triggered by infections; the neurological disorder Guillain-Barre Syndrome, for example, can be initiated by a Campylobacter jejuni infection. Given the wide-array of immune-related conditions which may result from a COVID-19 infection, this will remain an area of active research.

Onset Of PANDAS

Diagnostic criteria for PANDAS were put forth in the late 1990’s, but no accepted lab test or biological markers have been identified. This poses a challenge when working with real-life patients in a clinical setting.

How soon after strep infection do you start to see OCD symptoms in a child living with PANDAS? Families of patients present to Dr. Williams’ and Dr. O’Dor’s clinic and report that their child had rapid onset OCD symptoms in association with a strep infection. Some families report a positive strep infection 6 weeks prior to the onset of symptoms, but some families report that the infection began 3 months prior to the onset of symptoms. Some families report rapid onset OCD symptoms, and will have a co-existing strep infection without even realizing it. In the case of a strep infection several years prior to the onset of OCD symptoms, it is difficult to know for sure if this is a presentation of PANDAS.

Generally, the OCD symptoms begin after the strep infection has cleared, often after a patient has been given antibiotics. This is why we think PANDAS is the immune response to strep infection rather than a toxin related to the strep infection in itself.

How Is PANDAS Diagnosed?

In PANDAS cases, the “chief concern” of most parents is how rapidly and significantly their child has changed. The behaviors were never there before, and now the child’s new behaviors dominate all household dynamics.

When Dr. Williams meets with a child and their family reporting new onset OCD symptoms in the presence of recent strep infection he asks the following questions:

Did the child have a confirmed GAS test?

This is necessary for diagnosis of PANDAS

Has the child ever had any anxiety, OCD, movement, tic disorders in the past?

To meet clinical criteria for PANDAS, the episode closest to the recent positive strep test should be the first episode

How quickly do symptoms go from nonexistent to extremely severe?

Most of the time in PANDAS, symptoms go from nonexistent to extremely severe over the course of one week. This is vastly different from OCD (and most other psychiatric disorders) which has a more insidious onset.

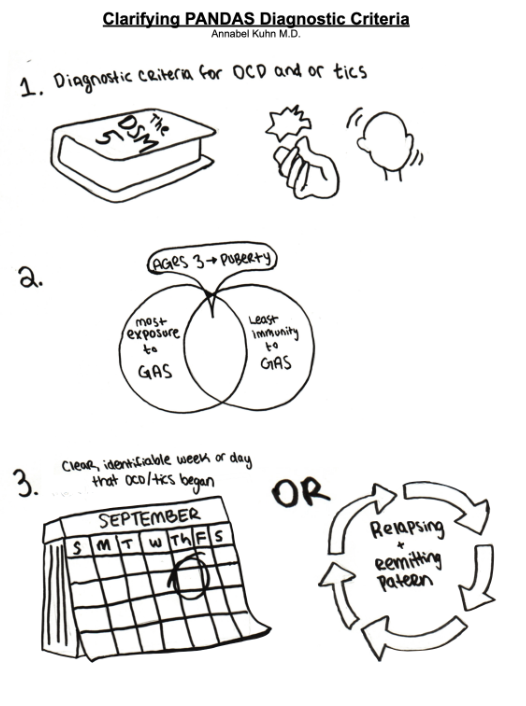

Diagnostic criteria for PANDAS is as follows:

Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and/or tic disorder (Tourette syndrome, chronic motor or vocal tic disorder) that meets DSM 5 diagnostic criteria.

Pediatric onset (between ages three and puberty)

Abrupt onset with episodic course of symptoms

Temporal relation between GAS and onset and/or exacerbation.

This timeframe was not specified in the original description.

Antibody levels to streptolysin O and DNase B remain elevated for several months after an acute infection, complicating the applicability and interpretation of elevated titers.

Neurologic abnormalities

Motoric hyperactivity such as fidgeting, difficulty remaining seated

Choreiform movements which are elicited through stressed postures such as standing upright with feet together and eyes closed, holding arms outstretched with hands extended. These movements are not present at rest.

Frank chorea (rapid, irregular, non stereotypic jerks that are continuous while patient is awake but improves at sleep) suggests Sydenham chorea, not PANDAS.

Considering adding information about other ancillary symptoms, like separation anxiety, fine motor deterioration

How Is PANS Diagnosed?

In order to meet clinical criteria for PANS, children do not require a positive strep test. To meet clinical criteria for PANS, children need to have new onset OCD, restrictive eating, or tics, as well as two or more of the following symptoms:

Sudden worsening of handwriting

Difficulties with sleep

Mood lability

Aggression

Difficulty concentrating

Bedwetting

We hypothesize that these symptoms occur in PANS as a result of a change in the cortical striatal loops which have an impact on executive functioning, motor circuitry, and motivation. The average age of onset of PANS is 7-8 years. Most of the children diagnosed with PANS have not had any developmental delays. A PANS diagnosis represents a sudden decrease in previously adequate social and motor functioning which occurs after an infection and in conjunction with new onset OCD, restrictive eating, or tics symptoms. With appropriate treatment, these symptoms resolve and the child’s social and motor functioning return to their previous baseline.

Can Any Child With OCD/Tic Disorder Who Gets Strep Throat Meet Diagnostic Criteria For PANDAS?

No. In a prospective study from 2002, twelve children with PANDAS were identified in a primary care setting over the course of three years. Each child had positive throat cultures at the time of onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms. They each had improvement of neuropsychiatric symptoms with antibiotic therapy. In four out of the twelve patients, symptoms resolved completely within 5 to 21 days after onset, and none of the four had recurrence of symptoms. Recurrent neuropsychiatric symptoms developed in the remaining eight children, and each recurrence was associated with a new episode of culture-proven group A strep tonsillopharyngitis. In each recurrence, the neuropsychiatric symptoms resolved with antibiotic therapy.

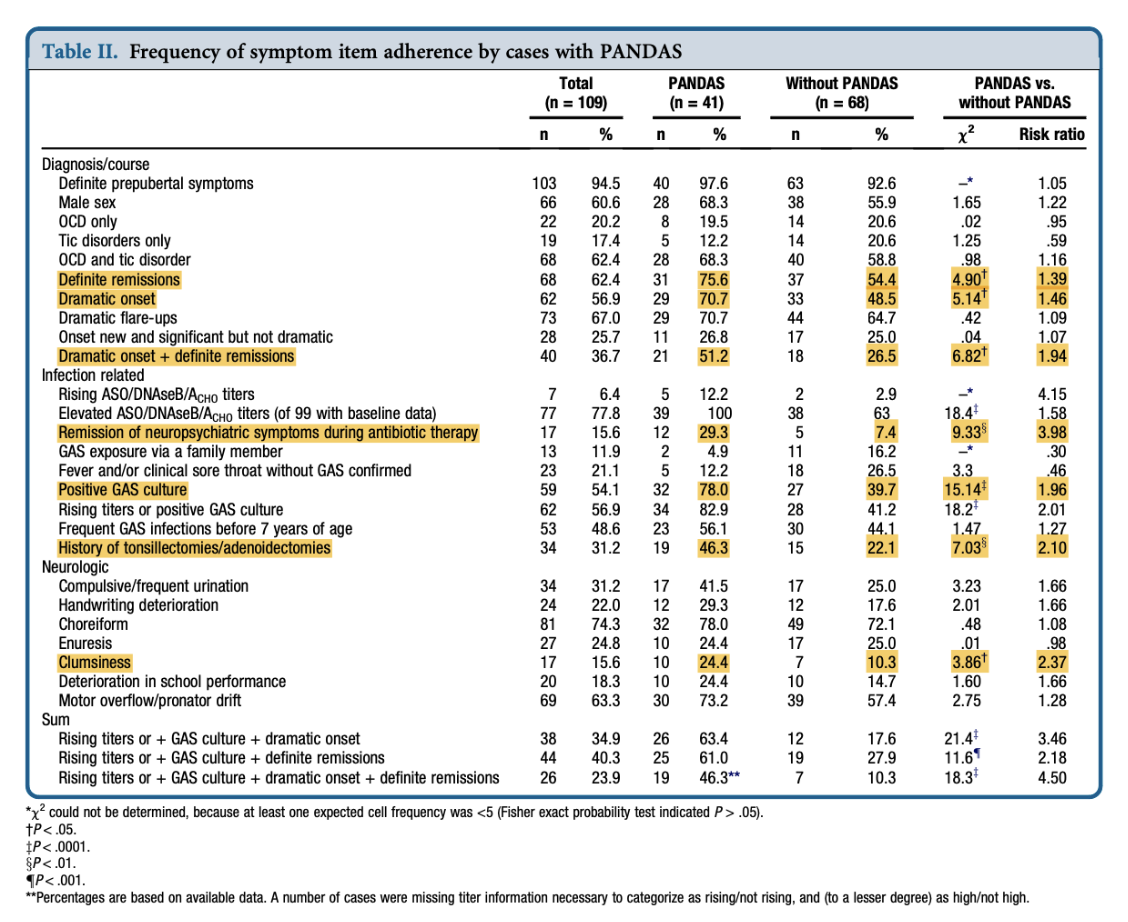

A study from 2012 assessed 109 prepubertal children with tics, OCD, or both. The children were examined with personal and family history, diagnostic interview, physical examination, medical record review, and measurement of baseline levels of streptococcal antibodies. Significant group differences were found on different variables such that children with PANDAS (versus without PANDAS) were more likely to have had:

Dramatic onset

PANDAS vs. without PANDAS (χ² 5.14 P < .05, Risk Ratio 1.46)

Definite remissions

PANDAS vs. without PANDAS (χ² 4.90 P < .05, Risk Ratio 1.39)

Dramatic onset + definite remissions

PANDAS vs. without PANDAS (χ² 6.82 P < .05, Risk Ratio 1.94)

Remission of neuropsychiatric symptoms during antibiotic therapy

PANDAS vs. without PANDAS (χ² 9.33 P < .01, Risk Ratio 3.98)

History of tonsillectomies/adenoidectomies

PANDAS vs. without PANDAS (χ² 7.03 P < .01, Risk Ratio 2.10)

Positive GAS culture

PANDAS vs. without PANDAS (χ² 15.14 P < .0001, Risk Ratio 1.96)

Clumsiness

PANDAS vs. without PANDAS (χ² 3.86 P < .05, Risk Ratio 2.37)

Table 2 from Murphy et al, 2012

How Do We Treat PANDAS?

Anti-inflammatory medication and antibiotics

The most important and most beneficial treatment for kids with PANDAS is an antiinflammatory medication. First line option is naproxen sodium (also known as aleve). This is preferred to ibuprofen because naproxen only requires twice daily dosing, whereas ibuprofen requires three times daily which could pose a challenge for adherence. Steroids are not recommended as antiinflammatory therapy in children with PANDAS due to significant side effects.

Dr. Williams and Dr. O’Dor have an ongoing trial observing naproxen and treatment of PANDAS symptoms in children. They began this study due to working with many children with PANDAS who have been empirically treated with naproxen with good effect. Anecdotally, it seemed as though children who had the best response to treatment with naproxen were those who were treated closest to the time of onset of symptoms. Preliminary data is not available at this point as this is an ongoing trial.

Dr. Williams advocates for the appropriate use of antibiotics in the treatment of PANDAS. He says antibiotic treatment should not be indefinite, and most children do not require prophylactic antibiotics. The antibiotics used for PANDAS include amoxicillin, cefalexin, and azithromycin if a patient is allergic to penicillin/cephalosporins. Amoxicillin and cefalexin act by modulating glutamate transporter genes. The effect of glutamate seems to be beneficial in short-term treatment of OCD symptoms in children with PANDAS. Azithromycin has a known anti-inflammatory effect, which may also be involved in the treatment of PANDAS. Antibiotics have been explored for the treatment of other psychiatric disorders. For example, ceftriaxone has been studied in the treatment of depression as well as Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS).

Dr. O’Dor shares that it is important to avoid feeling isolated and defeated. Even though PANS/PANDAS is rare, it has happened to many families.

Treating GAS infection

Antibiotics are recommended for treatment of acute strep infection (diagnosed with positive throat culture, rapid antigen test, or positive skin culture from infected skin). Antibiotics should be used to treat GAS infections whether or not neuropsychiatric symptoms are present. Antibiotic therapy reduces severity and duration of symptoms, reduces risk of complications (including risk of acute rheumatic fever), and reduces risk of transmission.

Treating GAS in PANDAS

Children with suspected PANDAS (abrupt onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms and evidence of recent GAS infection) should be treated with antimicrobial therapy even if the episode of GAS was already treated. This is because Murphy et. al. 2002 (as discussed earlier) demonstrated resolution of neuropsychiatric symptoms following treatment with antibiotics.

Treating neuropsychiatric symptoms in PANDAS

Swedo 2004 recommends neuropsychiatric treatment with standard pharmacologic and behavior therapies. OCD symptoms respond to a combination of pharmacotherapy and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), particularly CBT with Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP). Motor and vocal tics can be treated with medications.

What Does Not Work For Treatment Of PANDAS?

PANDAS remains a controversial disorder, and some healthcare providers have strong opinions about whether PANDAS is a “real” disorder or not. Healthcare personnel sometimes give unwelcoming responses to parents when this disorder is mentioned, which leads parents to explore their own treatment options. Parents turn to the internet and discuss with other parents of children with PANDAS to seek treatment options. We as healthcare providers can help patients and families by referring them to providers who can provide appropriate treatment.

Dr. Williams recommends against the following treatments for PANDAS:

Elimination/restriction diets (unless a child has a specific gluten allergy which is separate from PANDAS)

CBD (cannabidiol)

Supplements such as turmeric

Is IVIG Used To Treat PANDAS?

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is an intravenous infusion of IgG antibodies. These antibodies come from highly screened donors. The antibodies used in the infusion come from several donors, not just a single person. High dose IVIG is an effective treatment for autoimmune conditions such as Kawasaki disease or immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP).

It was hypothesized that PANDAS might be an autoimmune or inflammatory disorder, and therefore might respond to IVIG. There have been two blinded trials exploring IVIG for PANDAS. The first blinded trial from Sue Swedo and Susan Perlmutter compared IVIG to plasma exchange (another type of autoimmune therapy in which antibodies are removed from a patient’s bloodstream). They compared IVIG, plasma exchange, and sham IVIG in children with PANDAS. The study demonstrated that 6 weeks after treatment, children who received IVIG and plasma exchange both had significant benefit in OCD and tic symptoms compared to the children who received sham IVIG. The children who had received sham IVIG did not demonstrate improvement after 6 weeks. They were then given IVIG, and their OCD and tics symptoms subsequently improved. This was the first evidence that IVIG is effective. This study was published in 1999, but did not quite catch onto standard psychiatric practice, most likely because psychiatrists do not typically prescribe IVIG. Furthermore, IVIG is expensive and can cost around $10,000 per treatment. This significant cost was not covered by insurance companies as the companies still considered IVIG “experimental”.

Dr. Williams published results from a 2016 randomized controlled trial of IVIG in PANDAS. The first phase of the study explored IVIG versus sham IVIG. He found that there was more improvement in the IVIG group compared to the sham group, but it was not statistically significant. There was tremendous variance between those who responded to IVIG and those who did not. For example, some children given sham IVIG demonstrated radical improvement. The second phase of the trial was open-label. Those who did not improve following the first phase (whether or not they had received IVIG) were offered open label IVIG treatment. Some children received their first dose of IVIG at that time, other children who hadn’t responded to IVIG originally received a second dose of IVIG. 80% of these children who were given IVIG in the second phase improved dramatically. This demonstrates that IVIG treatment is quite nuanced. The study seems to suggest that there is a better response when someone knows what treatment they are receiving.

In July of 2021, Dr. Williams co-authored a paper exploring if there were differences in brain structure that resulted in different responses to IVIG. They found strong evidence for striatal cholinergic interneurons as a critical cellular target that may contribute to pathophysiology in children with rapid-onset OCD symptoms, such as what occurs in children with PANDAS. In the study, they took serum from children with PANDAS who were in that 2016 trial, and infused it into mouse brains. They were looking to see if children with PANDAS had autoimmune antibodies that could bind to mouse brains, as mouse brains are similar to human brains in terms of protein structure. As it turned out, there were in fact antibodies that bound to a certain type of neuron, the cholinergic interneuron, in the basal ganglia of mice. Fortunately, the cholinergic interneuron has a distinct shape, which allows for easier examination. They combined a fluorescent antibody (one which they already knew bound to the cholinergic interneuron) and serum from a child with PANDAS. If both serum and antibody were bound to the same structure, they know they have found the cholinergic interneuron. Serum from children with PANDAS binds to this neuron, whereas serum from healthy control children does not bind to this neuron. This was replicated in the human brain, and it does in fact bind to human brain cholinergic interneuron as well. After treatment with IVIG, binding to the cholinergic interneuron decreased. They used serum from the PANDAS children at multiple time points, and antibody decrease in bloodstream correlated with symptom decrease.

If we were to go back and explore why IVIG failed in some children in the blinded phase of the 2016 study, it could be that children with low levels of antibodies might not respond to IVIG, but they might respond if they have higher antibody levels. Dr O’Dor and Dr Williams have been involved in starting an IVIG multicenter trial, and they are planning to onboard participants soon.

What Advice Would You Give To Front Line Providers?

Listen to parents and be open minded. Families go to an average of three providers before their child is diagnosed with PANDAS. A third of children with PANS/PANDAS present to the ER because symptoms are so severe. These families are under a lot of stress and distress, so taking the time to listen to their stories and understand their symptoms is key in linking them to an appropriate provider. Only practice within your comfort zone. If you see a case of new onset OCD and suspect PANS or PANDAS and it is out of your comfort zone, reach out to a different provider. Relatedly, if you are not comfortable prescribing naproxen or antibiotics, don’t prescribe it, refer out.

For more resources about PANDAS:

Pediatric Neuropsychiatry and Immunology Program at MGH: https://www.massgeneral.org/children/pediatric-neuropsychiatry-and-immunology

PANDAS Physician Network: https://www.pandasppn.org/

International OCD foundation: https://iocdf.org

Acknowledgments: This article was supported by “Mental Health Education & Research”.

References:

Brody, A. L., Saxena, S., Stoessel, P., Gillies, L. A., Fairbanks, L. A., Alborzian, S., ... & Baxter, L. R. (2001). Regional brain metabolic changes in patients with major depression treated with either paroxetine or interpersonal therapy: preliminary findings. Archives of general psychiatry, 58(7), 631-640.

Dileepan, T., Smith, E. D., Knowland, D., Hsu, M., Platt, M., Bittner-Eddy, P., Cohen, B., Southern, P., Latimer, E., Harley, E., Agalliu, D., & Cleary, P. P. (2016). Group A Streptococcus intranasal infection promotes CNS infiltration by streptococcal-specific Th17 cells. The Journal of clinical investigation, 126(1), 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI80792

Köhler-Forsberg, O., N Lydholm, C., Hjorthøj, C., Nordentoft, M., Mors, O., & Benros, M. E. (2019). Efficacy of anti-inflammatory treatment on major depressive disorder or depressive symptoms: meta-analysis of clinical trials. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica, 139(5), 404–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13016

Murphy, M. L., & Pichichero, M. E. (2002). Prospective identification and treatment of children with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with group A streptococcal infection (PANDAS). Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 156(4), 356-361.

Murphy, T. K., Storch, E. A., Lewin, A. B., Edge, P. J., & Goodman, W. K. (2012). Clinical factors associated with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections. The Journal of pediatrics, 160(2), 314-319.

Orlovska S, Vestergaard CH, Bech BH, Nordentoft M, Vestergaard M, Benros ME. Association of Streptococcal Throat Infection With Mental Disorders: Testing Key Aspects of the PANDAS Hypothesis in a Nationwide Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):740–746. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0995

Perlmutter, S. J., Leitman, S. F., Garvey, M. A., Hamburger, S., Feldman, E., Leonard, H. L., & Swedo, S. E. (1999). Therapeutic plasma exchange and intravenous immunoglobulin for obsessive-compulsive disorder and tic disorders in childhood. The Lancet, 354(9185), 1153-1158.

Sasson, Y., Zohar, J., Chopra, M., Lustig, M., Iancu, I., & Hendler, T. (1997). Epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a world view. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 58 Suppl 12, 7–10.

Swedo, S. E., Leonard, H. L., & Rapoport, J. L. (2004). The pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS) subgroup: separating fact from fiction. Pediatrics, 113(4), 907-911.

Williams, K. A., Swedo, S. E., Farmer, C. A., Grantz, H., Grant, P. J., D'Souza, P., Hommer, R., Katsovich, L., King, R. A., & Leckman, J. F. (2016). Randomized, Controlled Trial of Intravenous Immunoglobulin for Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated With Streptococcal Infections. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(10), 860–867.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.06.017

Xu, J., Liu, R. J., Fahey, S., Frick, L., Leckman, J., Vaccarino, F., ... & Pittenger, C. (2021). Antibodies from children with PANDAS bind specifically to striatal cholinergic interneurons and alter their activity. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(1), 48-64.

Yaddanapudi, K., Hornig, M., Serge, R., De Miranda, J., Baghban, A., Villar, G., & Lipkin, W. I. (2010). Passive transfer of streptococcus-induced antibodies reproduces behavioral disturbances in a mouse model of pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infection. Molecular psychiatry, 15(7), 712–726. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2009.77